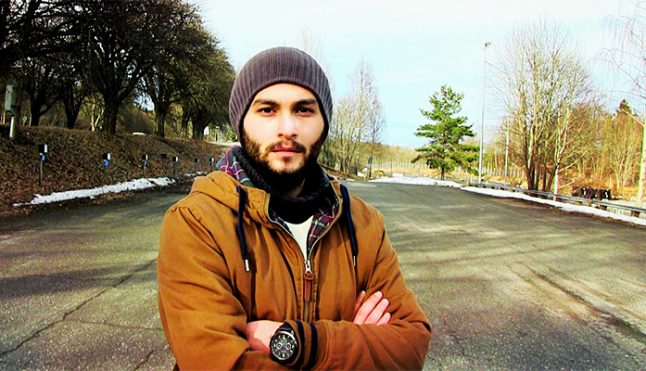

“The process of being reunited with family as a refugee has become very wearying and tragic,” says al-Tnnary, who first arrived in Sweden last September.

Recent changes to the law will make it more complicated for newcomers to be reunited with their families, making adjustment to the new country much harder.

“One guy who was with us in the camp recently travelled back to Syria – he had asked the Migration Board about his chance of seeing his family soon and they said it might take two years for him to get his asylum decision, then another two years before his family was reunited,” says al-Tnnary.

“That guy spent the days and nights at the camp talking to his kids and crying, until he finally had the chance to go back to them.”

He adds that the majority of Syrian asylum seekers hoping for their families to join them are stuck in a similar situation. Al-Tnnary's own wife is currently living in the United Arab Emirates, after she was stopped by customs officers at a Turkish airport on their journey, and banned from re-entering Turkey.

“She wants to come to Sweden, but we know that that’s close to impossible. It may take up to five years, and I haven’t even been interviewed for my asylum decision in Sweden yet.”

Having lost his ID documents at the Syrian-Turkish border, al-Tnnary knows it may take a long time for his application to be processed, and the Syrian regime won’t help him get new documents because he fled the country before carrying out his military service.

When the couple got married in Turkey, he was able to use the Kimlik ID (specifically for refugees granted temporary protection in Turkey), but it wasn’t possible to get the marriage authorized at the Turkish Foreign Ministry, meaning Swedish authorities may not legally recognize it either.

“I know there’s nothing I can do about it, this is my reality at the moment,” he says. “I have two choices: either present my marriage papers from Turkey to the Swedish authorities, and see if they’ll recognize them, or wait until I get my asylum decision and then re-marry my wife. There’s no third option.

“When Syrians try to cross the Turkish borders, you don’t know whether to proceed or turn back. In both situations you may get shot. It feels like that again; with both choices we are screwed. I don’t really know what’s going to happen to me here, and many Syrians feel the same – our future seems very uncertain and bleak.”

The 23-year-old has all but given up on starting a new life here, and says he has lost faith in the ability of Swedish authorities to process his case smoothly.

“Honestly, I hope the Swedish authorities reject my asylum application; that way I could leave the country and apply for asylum elsewhere. I have been living here for nine months and it’s changed me as a person, I feel like I have been totally destroyed.”

He went to the Migration Office to see if he could have his fingerprints removed from the system to cancel his asylum application – only once this was done would he be able to reapply in a different country.

The employee replied jokingly: “The only way to have your fingerprints removed is by having your fingers chopped off.”

“That came as a shock,” al-Tnnary says. “Having my asylum case rejected in Sweden would warm my heart.”

Photo: Private

He wasn't always so pessimistic about the future, and when he first arrived in the country, the young musician – whose most recent track is dedicated to his wife Lama's 22nd birthday – wanted to put the time spent waiting for his asylum decision to good use.

“In Europe I found there’s an overwhelmingly negative image of refugees – and sometimes the acts of a minority of refugees contribute to that. But we are like any other section of society – a mixture of different kinds of people – and no-one should generalize,” he says.

He began a video project, planning to film Swedes on the street, giving advice to pass on to newcomers.

However, he says he was soon “disappointed and discouraged” for a variety of reasons, including reluctance of many Swedes to get involved, as well as a lack of resources to take the project to larger cities.

“With my current situation I can’t think positively anymore. I ask myself, 'why should I contribute, when my life is ruined?' The only thing that I will be sad about if I leave is parting from the Swedes’ kindness and morality – they are very respectful and nice people,” al-Tnnary says.

“There are hundreds like me, maybe in worse situations. Many Syrians are waiting to reunite with their families, who might still be living under barrel bombing. I actually see myself as spoiled compared to them.

“I won’t stop waiting for my wife and I won’t give up. All we want is to reunite, settle down and live together. I am asking God to end the Syrians’ misery – it’s been going on too long.”

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.