Professor Ludvig Sollid and his team at the University of Oslo have discovered that coeliac sufferers have one of two defective human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) which cause the immune system to see gluten molecules as dangerous, triggering an immune response which causes severe inflammation and other symptoms.

“When a person who has coeliac disease eats gluten, the immune system reacts to gluten as if it were a virus or a bacterium,” Sollid told Norway’s NRK. “It attacks the gluten, and part of this attack causes the immune system attacks the body itself.”

HLAs are proteins which act as markers, binding to fragments of other proteins, and so telling white blood cells called T-cells how to treat them. The defective HLAs bind to fragments of gluten, fooling the T-cells into thinking they are bacteria or viruses.

“We think that this is huge,” Sollid said. “We understand the immune cells that are activated and why they are activated.”

Sollid carried out the research In collaboration with colleagues at the Centre for Immune Regulation at University of Oslo.

Coeliac disease can be a severe disorder, causing debilitating pain, chronic constipation and diarrhoea, stunted growth in children, anaemia and fatigue,

It was first described and named by Aretaeus of Cappadocia, a Greek physician practicing in the 1st century, but it wasn’t until the 1940s that it was linked to wheat consumption, and until 1952 that it was specifically linked to gluten.

DISEASE

Norway scientists find cause of coeliac disease

Norwegian scientists have discovered the cause of coeliac disease, the auto-immune disorder which causes gluten intolerance in about one in a hundred people

Published: 1 July 2015 00:12 CEST

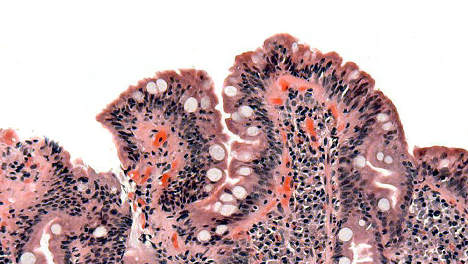

A biopsy of a small bowel afflicted by coeliac disease. Photo: ToNToNi/Wikimedia Commons

Url copied to clipboard!

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments