Grass, whose works include "The Tin Drum" and "Cat and Mouse", died in a hospital in the northern city of Lübeck, the Steidl publishing house said on Twitter.

Best known for his distinctive style of magic realism, Grass' most famous novel "The Tin Drum" was adapted into an Oscar-winning film by Völker Schlöndorf in 1979.

A prolific writer of novels, poems and plays over a period of decades, Grass constantly called Germany's past into question, and eventually received the Nobel Prize for Literature in the twilight of his career in 1999.

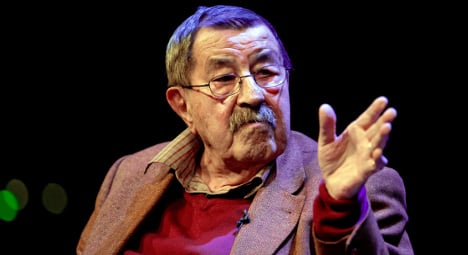

He became an intellectual icon in the second half of the 20th century, and was easily recognisable through his bushy moustache and ever-present pipe.

Born in 1927 in the Free City of Danzig, Grass grew up in a poor, Catholic family of Kashubian-Polish origin.

He was conscripted into the army in 1944 at the age of 17, and in 1945 served briefly as a member of the SS, which he only revealed in 2006, to great controversy.

After the war, when his hometown had been captured by the Soviet army and annexed to Poland, he moved to West Germany where he would spend the rest of his life.

Grass' work was known for its left-wing political dimension, as well as for its stylistic innovation. He was an active supporter of the Social Democrat Party (SPD) and was heavily involved in a number of Willy Brandt's election campaigns. He was an artist truly engaged with his era.

A self declared humanist who disliked ideologies, Grass rarely shied away from taking up a strong position on an issue.

He was a fierce critic of the installation of nuclear missiles on German soil in the 1980s. He was more recently strongly critical of Israel, and even opposed German reunification.

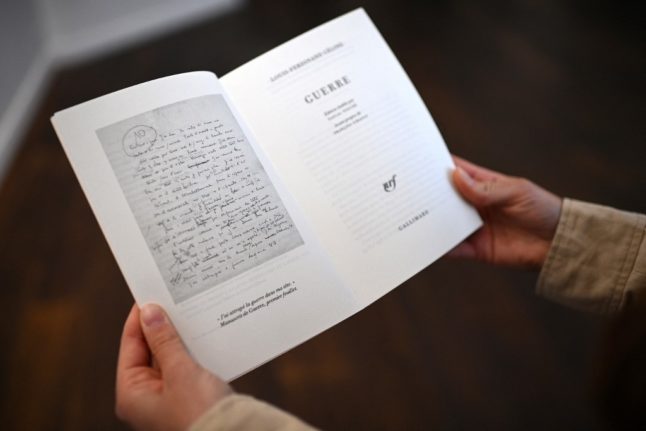

His novels were often just as provocative, striking, and at times grotesque. Powerful and raw, rather than polished, his style was a unique one. For example the original manuscript for "The Tin Drum" contained lots of errors.

Salman Rushdie, no stranger to controversy himself, tweeted a heartfelt tribute:

This is very sad. A true giant, inspiration, and friend. Drum for him, little Oskar. https://t.co/5b4Y7fTtin

— Salman Rushdie (@SalmanRushdie) April 13, 2015

"The Tin Drum" breathed new life into Germany's difficult recent history. Grass' masterpiece is founded on the retelling of the events of the Nazi period, the invasion of Poland, and post-war Germany through the skewed lens of unreliable narrator Oskar Mazerath.

Oskar, who tells the story from a mental institution, decides at the age of three to stop growing, and goes on to live through his surreal, magical version of German history from the 30s to the 50s, all the while playing his beloved tin drum.

Writing in Spiegel, Sebastian Hammelehle puts Oskar Mazerath up with the truly great characters of German literature – Faust and Mutter Courage.

The novel was supported by "Group 47", a collective of writers and artists set up after the war, which included other greats like Heinrich Böll and Paul Celan.

So strange, innovate, and at times shocking, "The Tin Drum" enchanted and outraged readers in equal measure. It was burned in Düsseldorf, and called blasphemous and pornographic by critics, but went on to become one of the definitive works of post-war literature.

His other works, including "Cat and Mouse", and "Dogyears", which alongside "The Tin Drum" formed the so-called "Danzig Trilogy", use similarly magical, surreal, and fairytale-like elements to deal with Germany's past and issues of the time.

Figure of controversy

Although much of Grass' work contained autobiographical elements – to the extent that he once described himself as "the sum of all his characters" – in an autobiographical novel "Peeling the Onion", released in 2006, he made a shocking revelation.

He admitted that he had been a member of the SS for two months in 1945. Previously he had been considered as a member of the generation too young to experience much fighting and to carry much responsibility for the Third Reich.

For someone so respected, who become a kind of moral authority, these revelations were deeply shocking. The fact that he had been so critical of the Nazi past, and yet concealed his own role, caused outrage in the German press.

Because he was only 17 at the time and was conscripted, some people have risen to his defence, saying that a mistake as a teenager should not damage the literary legacy of half a century.

Speaking to the BBC in 2006, Grass said: "It happened as it did to many of my age. We were in the labour service and all at once, a year later, the call-up notice lay on the table. And only when I got to Dresden did I learn it was the Waffen-SS".

Whatever is said about these revelations near the end of his life, Günter Grass will always be considered as one of Germany's greatest literary icons.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments