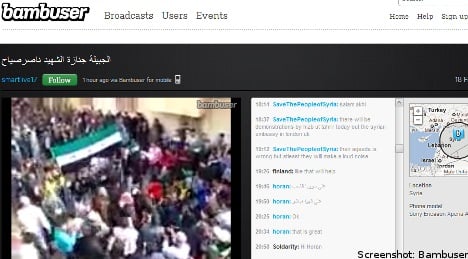

“Around noon yesterday (Thursday), we got information from our contacts in Syria that access to bambuser.com on the Syrian Internet and to the Bambuser mobile app for live streaming over Syrian 3G had been blocked,” company chairman Hans Eriksson told AFP.

“Dictators don’t like Bambuser,” he said, adding it appeared Assad’s regime

saw the site as a “major threat”.

Bambuser has for the past eight months been in close contact with the opposition in Syria, which uses its service to broadcast images of the escalating deadly crackdown, which otherwise would not be seen due to the international media blackout.

The site’s videos can be viewed through live-streaming, which means no downloading is necessary.

The company speculated that Thursday’s shutdown had come as a reaction to a

significant increase in the number of videos in recent weeks and especially to the live streaming of a video, shot by a local, of the bombing of an oil pipeline in Homs on Wednesday.

According to a Bambuser statement, the local had “live streamed the entire day, the black smoke that developed from the explosion with gunfire and shelling of Homs.”

“The footage was used by all the major networks. I think the Syrian authorities must have seen it to and understood the impact of it,” Eriksson said.

Although Bambuser’s services have been completely blocked on Syrian Internet and Syrian 3G, Eriksson pointed out that “of course the opposition have long ago formed ways around the Syrian Internet and Syrian 3G. They are very well organised and savvy with technology.”

He said he himself did not know all the techniques permitting regime opponents to continue to stream video despite the blockage, and that he in any case had vowed not to reveal their secrets to ensure they could continue to connect.

According to human rights groups, more than 6,000 people have died in Syria’s brutal crackdown on dissent over the past 11 months.

Bambuser has seen its services blocked previously, in Egypt in January 2011, and in Bahrain, where it has been offline for the past seven months.

The case of Egypt could give rise to hope though, Eriksson said, pointing out that when Hosni Mubarak’s regime blocked all connections intense pressure from international media had made it possible for Egyptians to get back online after four or five days.

“We hope the same kind of pressure will be put on Assad,” he said.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments