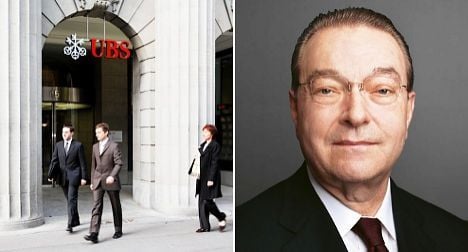

Sergio Ermotti has been named as interim CEO effective immediately, a bank statement said, nine days after the arrest of a trader accused of a $2.3 billion fraud at UBS.

While the board “regrets” Grübel’s decision UBS Chairman Kaspar Villiger said in the statement Grübel “feels that it is his duty to assume responsibility for the recent unauthorised trading incident.”

Villiger praised Grübel for “his uncompromising principles and integrity”, and acknowledged that during his tenure “he achieved an impressive turnaround and strengthened UBS fundamentally.”

The board also said it would “fully support” the independent investigation into the rogue trading and would ensure that “mitigating measures” were implemented to prevent such incidents from recurring.

Swiss media speculation had been mounting that Grübel would be ousted at the long-scheduled UBS board meeting held in Singapore in the run-up to Sunday’s Grand Prix — the bank is a major sponsor of Formula One racing.

Reports on Friday said Grübel was expected to seek a vote of confidence during the meeting, with the bank under pressure from shareholders and some Swiss politicians over the rogue-trading scandal.

On Tuesday, the Government of Singapore Investment Corp (GIC), UBS’ biggest shareholder, issued a rare public rebuke to the bank for lapses that led to the losses.

“GIC expressed disappointment and concern at the lapses and urged UBS to take firm action to restore confidence in the bank,” the cash-rich sovereign wealth fund said in a statement.

UBS had turned to Grübel, a former Credit Suisse boss, to stem its record losses amid the global financial crisis and seek a way out of its bitter tax evasion spat with the United States.

Grübel, 67, had engineered Credit Suisse’s own recovery in the early 2000s, after the bank took massive charges arising from the Enron scandal.

Within a year, the bank returned to profitability.

Likewise at UBS, Grübel managed to restore the bank’s profitability around 18 months after he took over the helm.

However, Grübel has now been forced to resign after UBS was hit with an internal crisis on his watch — the discovery of unauthorised trades allegedly made by trader Kweku Adoboli which lost the bank $2.3 billion.

Born November 13th, 1943 in eastern Germany, Grübel had entered the banking industry as an apprentice at Deutsche Bank.

His interim successor Ermotti had been appointed chairman and CEO of UBS Group Europe, Middle East and Africa in April, according to the UBS Investment Bank website.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.