A new review of document collections in the Swedish National Archives (Riksarkivet) shows that the arrest of the seven “Warsaw Swedes” by the Gestapo in Poland in 1942 not only seriously jeopardized the men’s lives but posed an existential threat to Swedish Match companies and other Swedish businesses throughout Eastern Europe.

The men’s release two years later was apparently secured not only through painstaking negotiations but payment of some type of compensation to Nazi Germany that included war materials.

The new information also casts Sweden’s wartime deliveries of ball bearings to Berlin in a new light.

After Germany invaded Poland in 1939, a group of Swedish businessmen from Swedish Match (STAB), LM Ericsson and ASEA joined the Polish underground and became its vital link to the Polish-government-in exile in London.

As feared, the activities of the so-called “Warsaw Swedes” were betrayed and in 1942 the Gestapo came calling.

Seven men were put on trial before the German High Court which on July 1, 1943 issued a stark verdict: four were sentenced to death, one to life in prison. Only two were acquitted but remained in custody.

In late 1943, the death penalty ruling was converted to life in prison, but the last of the men were not released until late November/December 1944.

Why the long delay?

That is the question former Swedish diplomat Göran Engblom addressed in a slim volume published in 2008.

The book called “Himmlers Fred” (‘Himmler’s Peace’) and published by Sekel offers an intriguing thesis.

Engblom argues that SS Chief Heinrich Himmler used the case of the ‘Warsaw Swedes’ as a way to gain concessions from Sweden to help him facilitate contact with Allied representatives in an effort to secure a separate peace agreement for Germany.

The Swedish businessmen’s arrest in 1942 had set off a tense two and a half year tug of war between Sweden and Germany, led on the Swedish side by Jacob Wallenberg (head of STAB’s Board of Directors), Alvar Möller, (director of STAB’s operations in Germany), Axel Brandin (STAB’s director in Sweden) and the Swedish Legation in Berlin.

Aside from Himmler, the main negotiators for the Nazis were German Intelligence Chief Walter Schellenberg and Himmler’s able masseur, Finnish-born Felix Kersten.

Kersten was the only person who could relieve Himmler’s chronic and painful intestinal spasms, a fact that made him ideally suited as an intermediary. The negotiations ultimately proved successful, although it has never been made clear what concessions exactly the Swedish side made to Germany for the release of the men.

Engblom suggests numerous attempts to secure a separate peace which occurred from mid-1943 through 1944 can be traced directly to Himmler attempting to facilitate neutral Swedish channels.

That however, may not have been the only form of compensation Sweden paid to Nazi Germany for the imprisoned men.

As historian Staffan Thorsell wrote in an essay in 2008, Nazi officials had stated point blank to their Swedish prisoners that to them they were “worth their weight in gold”.

Few people realize how enormous the financial stakes were for Swedish companies at the time, especially for Swedish Match.

Throughout World War II, STAB enjoyed monopoly status in Germany and Poland, as well as Romania, Hungary, Yugoslavia and the three Baltic States.

The monopoly contracts had been put in place in the late 1920’s and 1930’s by Swedish Match’s legendary founder Ivar Kreuger.

Through his company, Kreuger had granted these countries huge loans in exchange for the exclusive right to produce and sell matches for decades to come.

After Germany marched into Poland, the agreements remained in effect.

As documents in Riksarkivet show, Poland’s outstanding obligation to STAB alone at the time of the Warsaw Swedes’ arrest amounted to no less than $29 million (about $290 million in today’s value), based on a contract renewal dating from 1937.

With a variety of valuable assets at stake throughout Eastern Europe, Swedish Match and other companies stood to suffer enormous losses, amounting to tens, possibly hundreds of millions of US dollars, if German authorities had decided to take retaliatory action; either by confiscating Swedish holdings or by choosing to alter the terms of the respective monopoly agreements.

And Himmler initially considered precisely such “Zwangsmassnahmen”, (punitive steps) as he outlined in an internal memo dating from August 1942.

An essay that appeared in a special publication issued by the Wallenberg bank in 1972 underscores the existential threat STAB confronted in 1942.

As the author of the piece (Geal Elmér) put it: “There surely was no other company which had similar claims on states drawn into the war …”

And he added: “STAB’s goal was simply to survive.” So, both Swedish Match and the seven detained men were in serious trouble indeed.

And while their employers undoubtedly regarded the men’s efforts on behalf of the Polish underground as honorable, they also had seriously jeopardized company interests.

Thankfully, with Germany’s war fortunes declining rapidly from 1942 to 1944, Nazi leaders ultimately had a strong incentive to negotiate and to take advantage of both Sweden’s neutrality and its high quality industrial goods.

The first direct hint that Swedish business may have provided war materials such as ball bearings as concession for the release of its detained countrymen came in a 2006 publication by historian Staffan Thorsell (Mein Lieber Reichskanzler: Sveriges kontakter med Hitler’s rikskansli. Bonniers, 2006).

In the US National Archives, Thorsell discovered a post-war interrogation report by US officials who had debriefed high ranking SS-General Gottlob Berger.

In the interview Berger claimed that there had been a clear quid-pro-quo in the case of the ‘Warsaw Swedes’. Berger alleges that Schellenberg “… proposed that Himmler should release the Swedes if we received deliveries of ball bearings in exchange…. Those Swedes were later released.”

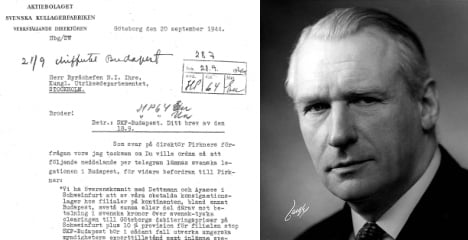

Interestingly, as Thorsell pointed out, in preparation for his war crimes trial in Nürnberg in 1948, Schellenberg made sure to list an “SKF man Holmberg” as a reference. This was almost certainly SKF Director in Gothenburg, Harald Hamberg.

And it was in fact Hamberg who in September 1944 issued rather astounding and previously little noticed instructions to SKF’s European affiliates: he ordered that all of SKF’s inventories on the continent at the time be handed over to German authorities.

This meant not only SKF’s holdings of ball bearings in Germany itself, but in all countries under German occupation.

This decision came right before SKF in October 1944 finally committed itself to stopping all ball bearing deliveries to the Nazis.

Since the spring of that year the US and Britain had applied ever mounting pressure on Sweden to halt supplies of all essential war materials to Hitler’s forces, yet deliveries to Germany had continued.

As is noted in the special Wallenberg publication from 1972, for SKF, 1944 marked “the most troubling period.”

The text explains that the company finally succeeded in “satisfying the Allies with different compromise solutions, preventing for a long time an open rift with Germany”.

SKF’s highwire act of balancing competing demands appears in a new light if viewed against the backdrop of the ongoing discussions about the imprisoned Swedish businessmen and the precarious position of Wallenberg businesses in Eastern Europe: the Allies in essence demanded that Wallenberg representatives cease the one negotiation advantage they had in their hand vis-a-vis Germany (namely, delivery of war goods) in the effort to save their men and their companies’ future.

Jacob Wallenberg’s reticence to give that up becomes clearer when one remembers what his companies stood to lose.

It is possible that Hamberg simply intended for SKF to meet the October 1944 deadline.

However, it certainly was a brazen act at a time when the Western allies were in no mood to see Sweden leave Germany with a parting gift of this magnitude and one that had the potential of prolonging hostilities.

The handover of SKF’s complete European inventories in late 1944 should be examined further, to see if this constituted the quid-pro-quo Gottlob Berger claimed did occur as part of a larger deal to save the ‘Warsaw Swedes’.

Unfortunately, Wallenberg family and company archives remain inaccessible to researchers on this point.

Germany never revoked Swedish Match’s monopoly contract.

In fact, after the war Germany continued to pay off its own sizable loan dating back to 1930, with the final installment paid only in 1983 by the then Federal Republic of Germany.

Swedish Match also successfully negotiated with the Soviet Union for lost assets and business after Stalin nationalized STAB and other Swedish companies’ holdings in the late 1940s.

The discussions, however, were tedious and lasted in some cases well into the 1950s and 1960s, casting a shadow into the early Cold War years.

It may have also complicated the already complex efforts to secure Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg’s release from Soviet captivity.

Susanne Berger is a historical researcher and former consultant to the Swedish-Russian Working Group that investigated Wallenberg’s fate in Russia from 1991-2001.

Ingela Magner is a Swedish writer and film director currently working on a cinematic adaptation of the story of the “Warsaw Swedes”.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments