The protest in Paris was one of around 200 around the country on Thursday but only drew around 40,000 marchers.

It could be seen and heard from far away, as drums were banged and chants were sung, marchers made their way towards the historic Place de la Bastille.

The chants of “SMIC à €2,000” (minimum wage at €2,000) and “Rétraite à 60 ans” (retirement at 60 years old) were repeated over and over.

Originally Thursday’s inter-union protest – representing workers from several sectors – intended to demand higher wages amid the cost of living crisis, but the mobilisation quickly shifted to focus equally on denouncing plans by President Emmanuel Macron’s government to push through pension reform.

Protests occurred as the French government vowed on Thursday to push through the reform by the end of the winter.

Macron made raising the retirement age from its current level of 62 one of the key planks of his re-election campaign, arguing that the current system was unsustainable and too expensive.

But opposition parties have vowed to fight the government all the way.

“It’s the start of a social battle,” leading left-wing MP Alexis Corbiere from the France Unbowed (LFI) party told AFP as he took part in a protest march of tens of thousands in Paris. “My hope is that this is the starting point.”

While there were some notable absences from the march in Paris, namely the largest union in France, CFDT, those present were keen on making their voices heard, particularly in regard to their plans to continue protesting should Macron push on with his plan to raise the retirement age.

“There is nothing wrong with the system as it is,” said Fréderic Aubisse, a sewage operator in Paris and former head of the waste treatment union with CGT. For Aubisse, the problem of salaries and retirement are connected – he sees current salaries as too low and unattractive.

“We just need more people paying into the system,” the former union head said.

For waste treatment workers, the subject of retirement is particularly sensitive.

“We [waste treatment workers] already have a low life expectancy,” he added, explaining that pushing retirement back even further is not sustainable for people in his line of work. In Aubisse’s view, many would die before getting to enjoy any benefits of retirement.

According to Libération newspaper, waste treatment workers in France do have an excess mortality of 97 percent.

Aubisse said he has been fighting for at least thirty years to keep social protections from being eroded, and that he and members of his union would continue protesting.

“If it makes it through parliament, it will be too late. We must start taking action now.”

Another demonstrator, Dominique, who has been employed as cash register worker for Carrefour supermarkets for 35 years, said for her it would be “like 2019 again.”

Dominique was referring to the 2019-2020 pension reform strike – the longest industrial action in French modern history. The Carrefour worker said she would be prepared to go to such lengths once more.

“Many of us here today have painful, repetitive jobs. We cannot continue to the age of 65,” said Dominique.

With deficits spiralling and public debt at historic highs, Macron views pushing back the pension age as one of the only ways the state can raise revenues without increasing taxes.

He has made it clear he would not hesitate to call fresh elections if opposition parties voted down the government over the reform.

Maintaining the focus on salaries

Some protesters in Paris on Thursday remained firm in the original motive of the protest to focus on demanding higher wages. The inter-union group, largely represented by the union CGT, called for for salaries to be indexed at a rate of at least 10 percent for civil servants.

The government previously increased the rate by 3.5 percent, but unions said that this “falls short of the urgent need to raise all salaries” and “preserve living conditions of all.”

Whilst the strike on Thursday caused some disruption on public transport and rail services, around one in 10 teachers joined the action forcing many schools to close their doors.

Teachers – a well-represented group at Thursday’s protest in Paris – were adamant wages must increase further.

“[The government’s 3.5% increase] is not enough. It does not suffice,” said Clotilde, an elementary school teacher in the Paris region.

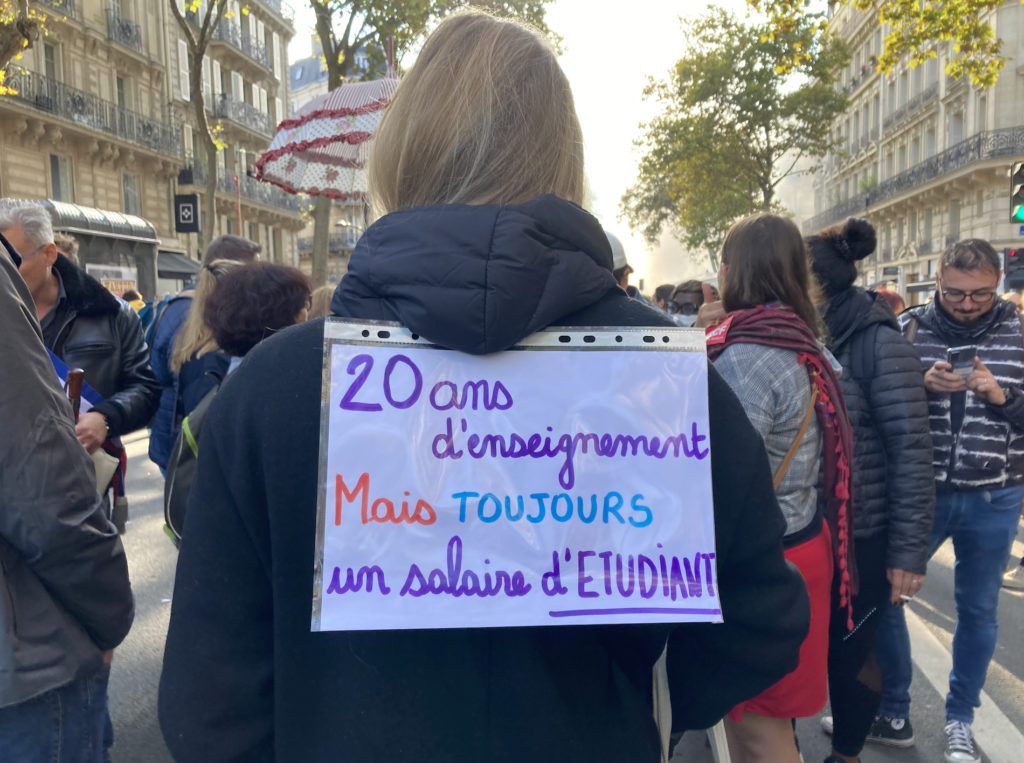

Wearing a sign on her back with the words “20 years in teaching, but still a salary of a student,” Clotilde said it is “extremely difficult to live in the Paris region as a teacher.”

For her, the government’s proposals did not adequately cover the costs of inflation, a sentiment which was echoed by fellow teacher Aina Tokarski.

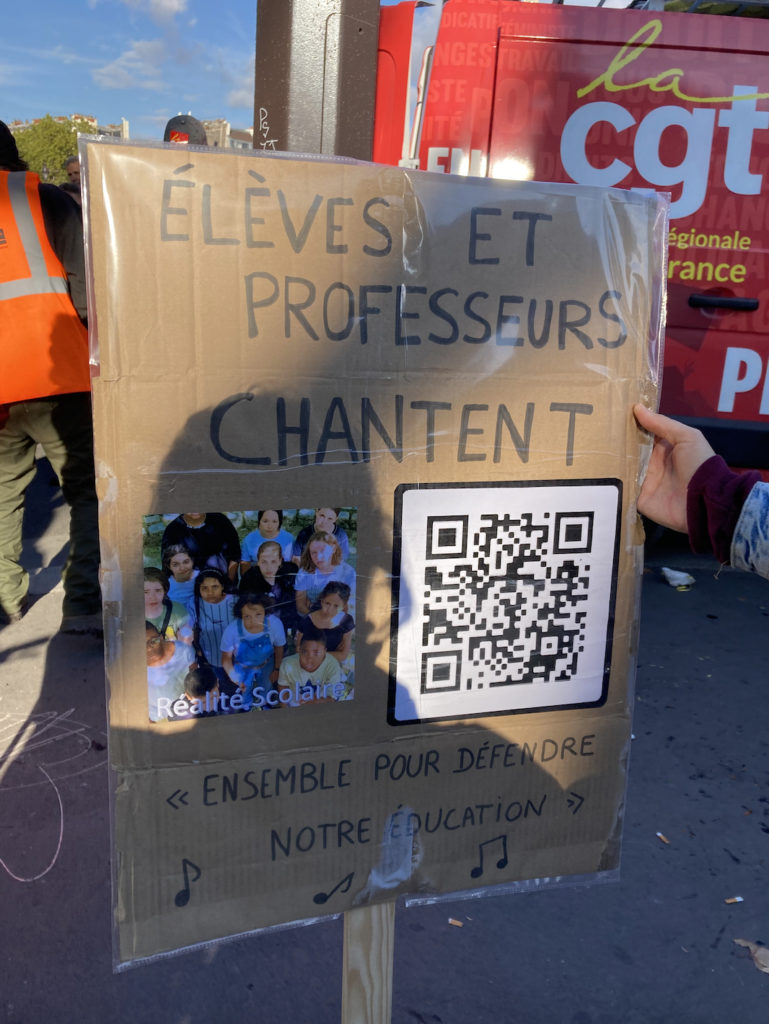

Tokarski, a middle school teacher in Villejuif, also wore her sign on her person.

Tokarski explained that the start of the 2022 school year shook her – a young teacher, she saw several colleagues leave the profession, and she too considered making some changes, such as moving to a more affordable region in France.

“When I get to the grocery store, I look at the prices and just think to myself: this is not possible,” she said.

For her, the government has not raised salaries enough to combat the cost of living crisis.

In addition to rising costs, Tokarski worries about the conditions in the public school system generally. “The start of the school year really concerned me. We have teachers with upwards of 30 students per class. That is unattainable. It has been getting worse since the pandemic,” she said.

While it was not a focus of the protest, other public employees highlighted staff shortages as deeply concerning, and innately related to salaries.

Véronique, a speech and language pathologist who works for the public hospital system, said she was there to “defend our salaries.”

Wearing a white doctor’s coat, Véronique explained that low salaries have pushed several doctors in her sector to leave their jobs, adding that this shortage has led to wait-lists growing far too long:

“It is not right for a four-year-old child who cannot speak to have to wait at least a year or two years to see a specialist. We have to triage our patients now,” she said.

When asked if she had plans to protest again, Véronique gave an emphatic “Bien sûr” (of course).

Xavier Signac, a 48-year-old member of the UNSA union from southwest France, as he walked along with a flag in Paris told AFP: “It’s up to us to show our determination, to show that street protests still have some power.”

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments