The Moors ruled much of Spain for almost 400 years from 711 to 1086, before they were driven south and continued their rule of southern Spain and the Kingdom of Granada for a further 400 more until 1492.

The series of century-long battles when the Christians tried to expel the Moors were known as the Reconquista (Reconquest), a term first coined in the 19th century.

However, many historians question the use of this word as Spain wasn’t formed as the nation prior to the Moorish conquest, and Muslim culture and knowledge contributed to what Spain is today.

Most of Spain wasn’t unified in fact until the marriage of the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragón and Isabella I of Castile, after the fall of the Kingdom of Granada in 1469.

It may have been long ago, but the Moors most certainly left their stamp on Spain, evident today from vestiges of their culture we can see in everything from the Spanish language and food, to its architecture and music.

Staunch Spanish nationalists, most notably far-right party Vox, would like to have everyone follow the narrative that Asturian hero Pelagius (Don Pelayo) and other medieval warriors took back Catholic Spain and restored it to exactly what it once was, shrugging off any benefit Muslim rule brought.

That, of course, does not tell the full story. So, what did the Moors ever do for Spain?

They developed Spain’s irrigation systems

The Moors built (and improved on those built by the Romans) thousands of kilometres of irrigation channels or acequias across Spain. These were not only used for agricultural purposes but also brought water to the cities and neighbourhoods, filling public fountains, providing drinking water, water for cleaning and water for washing before prayers at the mosques. Water was also an important symbol of purity in the Islamic rules and integral to their religion too.

They were great pioneers in medicine, pharmacology and science

The Moors founded modern hospitals, where they combined schools and libraries, as well as gardens for the cultivation of medicinal plants, and separate departments for ophthalmology, internal medicine and orthopaedics. Many modern health centres are still based on these models. The Muslim surgeons of the 11th century even knew how to treat cataracts and stop internal bleeding. They kept lists of plants to be used for medicines and pharmacology. One of the Moors responsible for one of the most important lists was Ibn al-Baytar, born in Málaga in 1197.

As for science, the Moors influenced all facets of the subject, from physics and chemistry to astronomy. They were the first to provide more scientific information on substances such as alcohol, sulphuric acid, ammonia and mercury, and were also one of the first people to create the distillation process. They were pioneers in the use of dams for the production of hydraulic energy and in the development of water clocks, which recorded time. With regards to astronomy, they built the world’s most important observatories in Córdoba and Toledo (as well as in the Middle East) and studied phenomena such as solar eclipses and comets.

They influenced the traditional music

The Moors greatly influenced Spanish music, particularly the soulful flamenco tunes. It’s said that the Spanish guitar can trace its roots back to the Arabic oud – a four-stringed instrument brought over by the Moors. Later, this was replaced by the guitarra morisca, the ancestor of modern Spanish guitars. The guttural sad tones of flamenco songs were also greatly influenced by the Moors and even today you can hear a strong resemblance to Arabic music.

They created a sewage system and public baths

Like the Romans before them, the Moors built many public baths. Hammams were very important to them both for ritualistic cleaning and social gatherings. At the height of the Moorish Empire in the 10th century, Córdoba was its capital and historians estimate that the city had around 300 public baths. Today you can see evidence of these bathhouses, all the way from Girona in the north, down to Málaga in the south. Several Moorish hammams have even been restored or faithfully recreated in cities such as Granada, Sevilla, Córdoba and even Barcelona.

In addition to baths, they also introduced some of the first sewer systems in Spain, where the dirty or used water was carried away through channels.

They set up Spain’s first universities

Islamic universities or madrasas were first created in the 11th century and were the forerunners to modern-day European universities. The first madrasa was built in 1349 in Málaga, which was followed by those built in Granada and Zaragoza, the latter dedicated almost exclusively to the teaching of medicine. In fact, classes here were still taught in Arabic up until the 16th century. The capital Córdoba, once had three universities, 80 colleges and a library with almost 700,000 manuscript volumes.

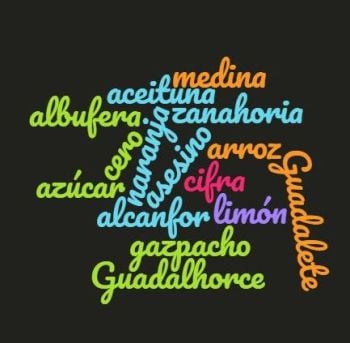

They shaped the language

Although Arabic and Spanish may seem like very different languages, there are quite a few words that the Moors in fact gave us. A clue is that many of these words begin with the letters ‘Al’, as in almohada (pillow), albóndiga (meatball) and algodón (cotton). According to linguists, it is estimated that around 4,000 Spanish words have some kind of Arabic influence, which equals to around 8 percent of the Spanish dictionary. Approximately 1,000 of those words have direct Arabic roots.

They designed incredible buildings

Today, some of the most-visited buildings in Spain are ones that were built by the Moors. The Moors built incredible structures, from regal mosques and ornate palaces to spectacular gardens. The most famous of these is of course Granada’s Alhambra Palace and Generalife Gardens. Built mostly during the 13th century, the Alhambra is one of the best surviving examples of Moorish architecture in the world. Other amazing Moorish buildings you can still visit today include Seville’s stunning Real Alcázar, Zaragoza’s Aljaferia castle-like palace, Córdoba’s grand La Mezquita mosque-turned cathedral and Málaga’s palatial fortress The Alcazaba.

They introduced popular games

Believe it or not, it was the Muslim rulers who introduced some of the world’s most famous games to Spain. According to historians, in 822, the Moors brought chess with them, which was originally invented in India. Thanks to Muslim influence, expressions such as checkmate have remained, which is derived from the Persian word al-jakh-mat or “the king is dead.” Another popular game, noughts and crosses or tres en raya as they say in Spanish, also comes from the Arabs, who called it the alquerque.

They added flavour to Spanish cuisine

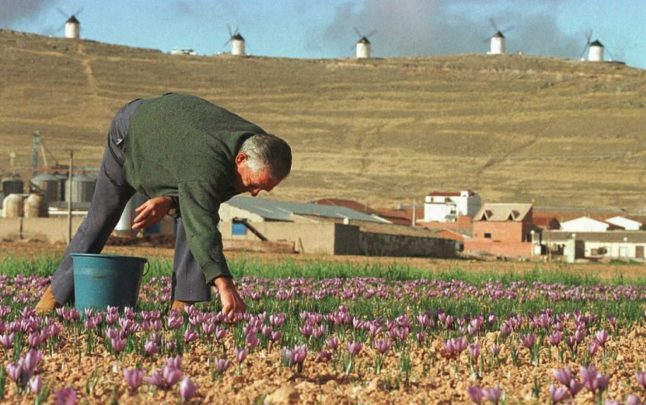

Spanish cuisine may not seem similar to that of Northwest Africa, but there are in fact many ways in which the Moors influenced the food in Spain and even some dishes which remain popular today. The main one is paella, as it was the Moors who first introduced and planted rice in Spain, as well as one of its main spices – yellow-hued saffron. Another dish that is in fact both eaten widely across Andalusia as well as in Morocco today is espinacas con garbanzos or spinach with chickpeas.

The Moors also introduced aubergine as seen in the much-loved Granada tapas dish – berejenas con miel (battered aubergine drizzled with honey or cane sugar syrup). They even introduced orange and lemon trees, such an important symbol of Spain today and used to flavour many dishes. And if it wasn’t for the Moors, the Spanish wouldn’t fry everything in olive oil.

So to slightly misquote John Cleese in Monty Python’s Life of Brian, apart from the Spanish guitar, paella’s ingredients, irrigation channels, universities, public baths, a sewage system science, mathematics, thousands of words, medicine, architecture and cuisine…what did the Moors ever do for us?

Written by Esme Fox and Alex Dunham

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments