In January 2022, it emerged that Spain had dropped in the global ranking of the 2021 Corruption Perception Index (CPI) compiled by NGO Transparency International.

It dropped two places since 2020, to 34th internationally, and has actually fallen four places, from 30th, in less than three years. Its new position places it 14th among the 27 European Union member states, and in the bottom three of Europe’s biggest economies: only Italy and Poland (tied for 42nd place) finished behind Spain.

But what explains Spain’s steady decline? Is there anything that can explain the drop, have other countries cleaned up their act, or is Spain really becoming more corrupt?

The rankings

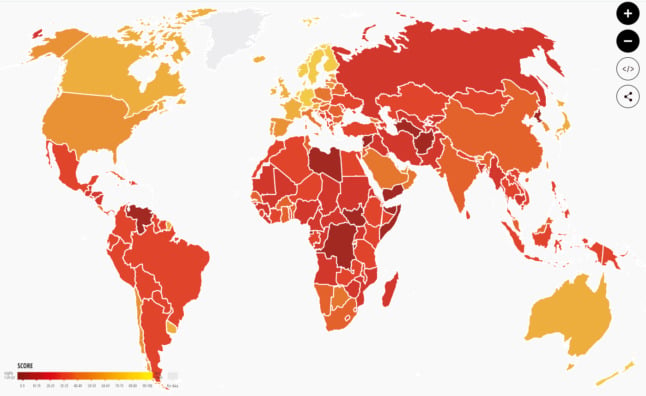

Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) ranks 180 countries and territories around the world by their perceived levels of public sector corruption. Each is given a corruption score on a scale of 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean).

Drawing on information sourced from survey data carried out by globally respected institutions such as the World Bank, the index considers several factors or indicators of bribery, studying how susceptible public institutions are perceived to be to bribery, embezzlement, officials who use public office for personal gain, institutions preventing anti-corruption and enforcement regulations, bureaucratisation and nepotism, among others.

One key takeaway from the 2021 Index is that corruption levels are stagnant worldwide, with “little or no progress” made in 86 percent of the countries evaluated in the index over the last ten years.

At the top of the perception list are Denmark, Finland and New Zealand, countries that, according to the Democracy Index, are also the top for civil liberties in the world. The countries who received the lowest scores, 11, 13, and 13, respectively, were Somalia, Syria and South Sudan.

Transparency International suggests that the world’s larger economies – such as Spain’s, which is among the top 15 in the world – should never receive a CPI score of below 70, especially if it wants to maintain its respect and competitiveness on the international scene. Yet in the 2021 CPI Spain received a 61/100, not only lower than the previous year but a score that places it below countries such as Chile, Uruguay, Lithuania, Estonia, the Bahamas, and Barbados.

Looking back

Using data available from past CPI studies, it becomes clear that Spain’s recent slip in the league table is not an anomaly but part of a longer-term trend. In 2000, Spain sat in 20th place with a score of 70 (or a 7.0, as the CPI was done on a 1-10 scale back then), and was neck and neck with countries such as France, Ireland, and Israel. Yet by 2005 it had slipped to 23rd place, albeit with the CPI score holding firm at around 70.

However, by 2010 Spain had dropped to 30th position, and its CPI score had dropped dramatically by 9 points to 61 (6.1 on the old scale). By 2015 the position had worsened, sinking to a score of 58 and flanked by Lithuania and Latvia, and in 2018 Spain ranked 41st in the world albeit with an unchanged CPI score of 58.

It seems clear that Spain’s CPI score had been in steady decline for the last two decades. Since the year 2000, the perception Spaniards have of their public institutions and actors – whether it be political parties and politicians, the police force, public administrations, and local ayuntamientos – and their susceptibility to corruption has worsened.

But the statistic that sticks out in the CPI data is the sudden drop in trust in public institutions from 2005 to 2010. Was there something specific that could explain such a change in public opinion?

Corruption in the news

The infamous Gürtel case is perhaps one famous corruption case that could explain both the sudden drop in public trust between 2005 and 2010, and the steady decline in more recent years. The Gürtel case, a case that engulfed right-wing party PP in accusations of money laundering, tax evasion, and bribery, came to light in 2009 but the main suspects were not put on trial, or even publicly named in some cases, until late-2016, both periods of time when Spain’s CPI score dropped.

The corrupt activities involved party funding and the awarding of contracts by local and regional governments in Valencia and Madrid, among others. Judges estimated the loss to public finances was a staggering €120,000,000.

Operation Kitchen has dominated the headlines in more recent years, and could also be a contributing factor in Spain’s falling position in the CPI. It also follows on and is connected to the Gürtel case, neatly tying together over a decade of corruption in PP.

Known as “Operación Kitchen” because the code name of the alleged informant was ‘the cook’, the informant worked as a driver for the former treasurer of the Popular Party (PP), Luis Bárcenas, who in May 2018 was sentenced to 33 years in jail for his role in a kickbacks scheme which financed the party known as, you guessed it, the Gürtel case.

The ruling led to the ousting of PP prime minister Mariano Rajoy in a confidence vote in parliament several days later. Public prosecutors allege the driver received €2,000 ($2,370) per month, as well as the promise of a job in the police force, in exchange for obtaining information regarding where “Bárcenas and his wife hide compromising documents” about the PP and its senior leaders.

The probe into “Operation Kitchen” is one of several which have been opened based on searches carried out following the arrest of José Manuel Villarejo, a former police commissioner who for years secretly recorded conversations with top political and economic figures to be able to smear them.

Of course, you can’t talk about corruption in Spain without talking about its royal family. Juan Carlos I, the now exiled former King of Spain (through personal choice), had a list of alleged corruption charges longer than a Spanish waiter’s order pad on a Saturday night: the Saudi rail payoffs, and money hidden in Swiss bank accounts; the mystery credit cards paid off by Mexican businessmen; the €10 million found in a Jersey bank account and, finally, his goat hunting trip with the President of Kazakhstan in which Juan Carlos left with armfuls of briefcases containing over €5 million in cash.

In March 2022, Spanish prosecutors dropped all investigations into his finances.

But corruption in Spain not only exists at the elite level; although the upper echelons of Spanish society – government, the royal family – have been tarnished by allegations of corruption, perhaps it is the perceived corruption of local and regional institutions that contribute to Spain’s falling CPI score.

Small town corruption is nothing new. In January 2022, a councilwoman in the tiny Alicante province beach town of Santa Pola was arrested on suspicion of taking up to €40,000 in bribes over several years, and handing out catering contracts for money and favours.

The ongoing environmental scandal at Murcia’s Mar Menor has also been stained by corruption allegations. Former Minister of Agriculture in the region, Antonio Cerdá, is facing up to six years in prison for fraud and embezzlement and his role in the pollution of Murcia’s Mar Menor lagoon.

Police forces across Spain are no better, it seems. As the Catalan Generalitat investigates several cases of corrupt Mossos in its police force, port authorities and Guardia Civil agents across Spain, including Catalonia and Algeciras in Andalusia, have been arrested for taking bribes to turn blind eyes to drug trafficking.

Even during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, local mayors across Spain and its territories were caught out using their position and influence to queue-jump and get vaccinations before vulnerable groups.

Looking ahead

Perhaps the combination of this low-level corruption, and the slow-term eroding effect it has on public trust in institutions, with the more high-profile national cases that envelop kings and politicians explains Spain’s steady decline in the CPI score.

Spain’s upcoming 2022 CPI rankings may be very telling following the more recent news that Spain’s Supreme Court has upheld jail convictions for two former Socialist leaders in Andalusia involved in the long-running ERE corruption scandal, a decision Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez has actually criticised.

READ MORE: Why is Spain’s PM defending politicians charged with corruption?

And Catalonia, despite the separatist ambitions of many of its politicians, appears no different from the rest of Spain in terms of political recent corruption, as the latest graft charges against the speaker of the Catalan Parliament Laura Borràs suggest.

Social media undoubtedly plays a major role in influencing public opinion, as it provides Spaniards with minute by minute, rolling twenty-four hour news coverage of every misdeed anyone in public life does that they didn’t have in the past.

Judging by the CPI data available, it does seem that public opinion in Spain is swayed by such events and coverage.

The noticeable drops in public trust in institutions between 2005-2010, and again around 2018, mirror major national scandals.

Perhaps Spain isn’t necessarily headed on the downward trajectory the figures would suggest, and it isn’t set to tumble further down the corruption league tables.

In fact, judging by the 2021 CPI rankings, Spain is on a downward trend.

A multitude of factors could contribute to the worsening public perception of corruption in Spain: greed, social media, a constant news cycle, small town politics, pay-offs, bungs, bribes, new major national scandals, more dirt on exiled former kings.

If Spain is to fully emerge more economically secure from the pandemic and the current inflation crisis, rekindle the trust between the public and its institutions, as well as live up to its position as one of Europe’s major players, it better hope that its culture of political corruption dies off soon.

Could a new generation of young and conscientious politicians be the solution?

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Non Spain has greatly improved in terms of its corruption.