Where flamenco got its name from is unclear

Did you know that the Spanish word to refer to the Flemish language spoken in Belgium is also flamenco? Some have linked the dance’s name to Spain’s 16th century conquest of Flanders and the Netherlands, but this seems unlikely as the dance wasn’t documented as an artform until three centuries later.

Some theories suggest flamenco got its name from the similarity between the dancers’ pose and a flamingo bird, while another hypothesis is that it comes from the Andalusí Arabic expression “fellah min gueir ard” to speak of a farmer without land, used to refer to gypsies in Andalusia.

The origins of flamenco are also shrouded in mystery

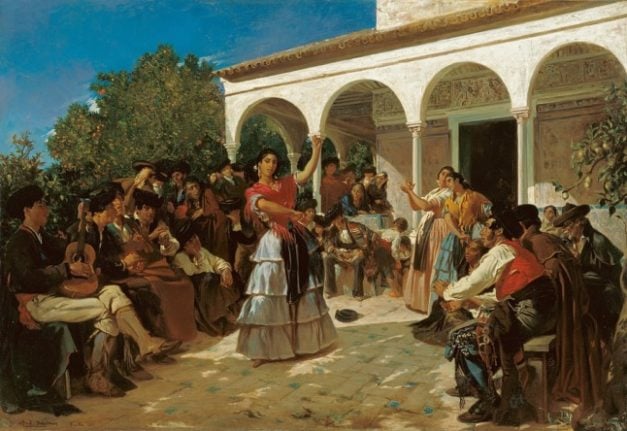

The general opinion is that Andalusia’s gitanos (gypsies) – who first arrived in Spain in 1425 as Christian pilgrims allowed in by King Ferdinand V of Aragon – were the creators of flamenco.

It’s believed that flamenco emerged in the 18th century in cities and villages of southern Andalusia such as Jérez de la Frontera, although other historians think its roots can be traced back to the Indian subcontinent where gypsies are thought to be originally from and where similar dances such as Kathak originated.

But the general consensus is that flamenco is an amalgamation of cultures and folkloric dances that began in Spain at around the time of the Reconquista – influenced by Christians, Muslims, gypsies and even Africans.

Napoleon helped to make flamenco quintessentially Spanish

Following the Spanish War of Independence in the early 19th century, in which Spain freed itself of Napoleon’s clutches, there was a push in Spain to embrace what was truly Spanish and shun French influences in language and culture.

This was known as casticismo, and gitanos’ flamenco dance together with the growth in popularity of bullfighting at the time in Andalusia, saw Madrid adopt these trends from southern Spain as representative of what it means to be Spanish, known as costumbrismo andalúz.

This trend reached its peak in the 50s and 60s in Spain thanks to flamenco’s greatest star – Lola Flores – who popularised the artform internationally as quintessentially Spanish.

For better or for worse, these stereotypes live on to this day, as flamenco and bullfighting only form a small part of Spain’s varied and rich culture.

Flamenco has its own language

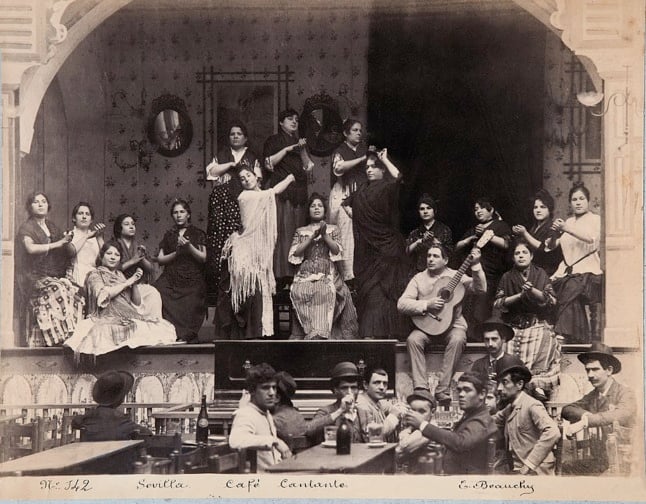

Flamenco incorporates four different elements: cante (voice), baile (dance), toque (guitar playing), and jaleo, which literally means making a racket or causing commotion but actually refers to the hand clapping and foot stomping.

Male flamenco dancers are called bailaores and females ones bailaoras, whereas any other dancers are called bailarín/bailarina in Spanish.

The flamenco ensemble are known as a cuadro (frame) rather than grupo (group) and the place where they perform is called a tablao.

To refer to the different styles of flamenco dance and song, the correct word is palos, which actually means sticks in Spanish. Then there’s the cante jondo which refers to the wailing that’s characteristic of more sorrowful flamenco singing.

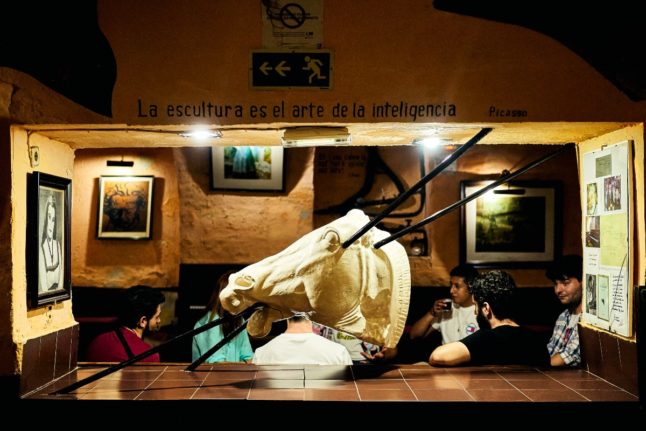

But perhaps the most interesting flamenco word is duende, which in regular speech means elf but in the context of flamenco refers to a mystical and powerful heightened state of emotion and expression which only the most gifted flamenco performers have.

Hands and shoes are musical instruments

Flamenco’s fast-paced Spanish guitar playing is what most outsiders are familiar with, but hand-clapping also plays an essential role in the artform.

Children who grow up in flamenco-loving families learn to finetune the art of hand-clapping and distinguish between hard (fuertes) and soft (sordas) claps. In other words, if they can’t sing, dance or play guitar, they’ll be expected to at least know how to dar palmas (clap).

Special flamenco shoes for both men and women provide the bailaores with another means of percussion other than the handclaps and the cajón flamenco (flamenco box drum).

However, castanets, which most people automatically associate with flamenco, are not a traditional element of flamenco performances, even though they are sometimes used to intensify finger snapping.

READ ALSO: Meet the New Yorker who moved to Spain to become a flamenco dancer

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments