Macron, in power since 2017, has not officially declared his candidacy for a second term – although it widely thought to be unlikely that he would not stand.

Voters in France go to the polls twice – after the first round the two highest-scoring candidates go through to a second round, and voters pick their favourite on a second polling day, two weeks after the first.

Candidates have until the beginning of March to formally declare so we could see some late surprises, but here are the main candidates so far.

READ ALSO Five minutes to understand the 2022 French presidential election

Emmanuel Macron – La République en Marche

The current incumbent has not yet officially declared that he intends to run, but analysts think it highly likely that he will and grassroots campaigning by his supporters has already begun.

A divisive figure in France he is nevertheless topping current polling (although a lot can change in a short time and opinion polls are not always reliable). His personal poll ratings hover at about 35 percent – which is unusually high for a French president this far into his term.

His party LREM, however, has failed to gain grassroots support and polled badly in local and European elections.

Marine Le Pen – Rassemblement National

The leader of the far-right Rassemblement National (National Rally, formerly the National Front) officially launched her candidacy at a rally in Fréjus, south east France, on September 12th, although she had previously said that she would stand.

Current polling shows that she, Macron and Valérie Pécresse (see below) are the most likely candidates to reach the second round of the elections, although Len Pen’s party has fared badly in recent local elections and some in the party have raised questions over her leadership.

Her platform has focused on immigration, crime and security.

ANALYSIS Which of the dozens of French presidential candidates have any chance of winning?

Valérie Pécresse – Les Républicains

The head of the greater Paris Île-de-France region was chosen as the official candidate of the centre-right Les Républicains party in their primaries on December 4th.

Socially conservative – she was heavily involved in anti gay marriage protests – she remains one of the more centrist LR candidates, especially on issued such as the economy, immigration and European integration.

She is the first female candidate ever to be selected by LR, the party of former president Nicolas Sarkozy.

An initial polling surge after her nomination as LR candidate appears to have faded, but she is still regarded as one of the favourites to make it through to the second round.

Anne Hidalgo – Parti Socialiste

The Socialist Party (PS) has been floundering since the one-term (2012-2017) presidency of François Hollande, who ended up so unpopular he did not even try to seek a second mandate.

That seems unlikely to change under Hidalgo, who is currently polling in single figures. She does at least have the support of party members, who officially voted to nominate Hidalgo as their candidate on October 14th.

Although her green and car-free policies proved popular enough to win her a second term as mayor of Paris in 2020, she may struggle to shed her image as ‘too Parisian’ for the rest of France (although she actually grew up in Lyon with Spanish parents).

Jean-Luc Mélenchon – La France Insoumise

The leader of the far-left La France Insoumise (France Unbowed) party was fast into the starting blocks and declared his candidacy in summer 2021.

Analysts believe he may struggle to match his effort from the 2017 edition where he was a major factor in the campaign and polled almost 20 percent in the first round.

Yannick Jadot – Greens

Europe Ecologie Les Verts (EELV) or the Green party held a primary to choose its candidate and party members plumped for MEP Jadot.

His task now is to transfer the dazzling success the Greens enjoyed in 2020 local elections, where they picked up several big city halls, to the national level.

Christiane Taubira – left unity candidate

Former justice minister Taubira won a ‘people’s primary’ of leftist voters, which was intended to united the divided French left under a single candidate. Unfortunately Hidalgo, Mélenchon and Jadot have all refused to recognise the legitimacy of the poll, so they result is even more division with another candidate added to the left of the political spectrum.

A talented orator with plenty of political experience, Taubira will now have to decide whether she will continue with her run in the face of deepening divisions and – as a latecomer to the race – come up with a policy platform.

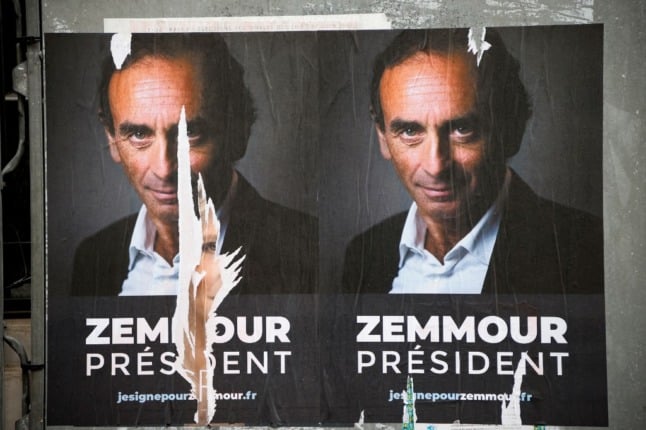

Eric Zemmour – far-right independent

The TV pundit formally declared on November 30th that he will stand for the presidency, making the announcement via a video posted online that references Brigitte Bardot, Johnny Hallyday and Voltaire.

Convicted of disseminating racial hatred, he has won a major following for his diatribes against migration and the Muslim headscarf and will pose a challenge Le Pen’s far-right hegemony.

His book on the ‘decline’ of France has been a bestseller.

Not running

Edouard Philippe

The former prime minister – who lost his job in July 2020 in a cabinet reshuffle after reportedly becoming too popular for his own good – had been considered as a possible candidate to challenge his former boss for the top job.

However on September 11th he formally declared that he would not stand, and would be supporting Macron in the 2022 race.

He has, however, launched his own political group – Horizon – with the declared aim of supporting Macron. He is widely believed to be preparing for a run at the Elysée in 2027.

Michel Barnier

The EU’s former Brexit negotiator announced his intention to stand for the presidency, but was beaten to the nomination for the centre-right Les Républicains by Valérie Pécresse. Also beaten in the primary were regional leader Xavier Bertrand, Philippe Juvin and far-right firebrand Eric Ciotti.

Arnaud Montebourg – L’Engagement

The former minister under Hollande entered the fray in September, vowing a remontada (rebound) for France, but in January withdrew from the race after poor poll ratings.

Seen as to the left of Hidalgo but more moderate than Jean-Luc Melenchon, he ran in left-wing presidential primaries in 2011 and 2017 but failed to win a nomination. Montebourg was this time backed by the new movement L’Engagement, named after a book he released in 2020.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments