Aside from the pandemic, the defining images of summer 2021 in Europe may prove to be weather related – from terrible wildfires in Greece to catastrophic flooding in Germany.

France has, so far, escaped the worst extremes but the country has already seen extreme heatwave and freak summer storms including hailstorms.

It’s common for France to experience storms following hot temperatures in July and August, even if the rainstorms came slightly earlier this year. But July saw 60 percent more rainfall than normal for the time of year.

“What’s exceptional is perhaps the fact that there were lots of examples of this type of event this summer,” Françoise Vimeux, climatologist at the Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD – French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development), told The Local.

“Flooding is not just linked to the quantity of rain, it’s also linked to where the rain falls, whether it’s on a surface which can absorb it, which is the case in the countryside, or whether it falls in a town, where urbanisation means that concrete grounds cannot absorb water which then runs off.”

Impact of climate change

Although it is difficult to know whether a single event was caused by climate change, the heating of the planet has certainly played a role, according to Vimeux.

“We know that heating up the atmosphere and the oceans exacerbates incidents of intense rain,” she said. “Why? Because when the temperature is higher, surface water is more easily evaporated, meaning oceans, seas, flooded areas, lakes.

“And the atmosphere is more capable of retaining this water when the temperature is high. We know that when the atmosphere warms by one degree, it can hold 7 percent more water vapour. So when a weather event comes and cools down this air mass, there’s a lot more water which can fall.”

READ ALSO Forecast: Will summer in France ever get going?

So as the planet heats up, should we get used to wet summers in France?

“The climate projections show that, overall in France, we should expect less rain during the summer,” Vimeux said.

“However, that doesn’t mean there won’t be extreme rains over a very specific period and very locally, because our atmosphere will be loaded with water.”

Orage d'une intensité incroyable et stationnaire sur la ville de #Beauvais qui à subi de graves inondations localement avec + de 100mm de plus en mm 1 heure hier soir. #meteo60 #orages #inondations #crues #violent #picardie #orage

Vidéo Samir pic.twitter.com/usPJNHOIe4

— Chasseur d'orages Lorrain – Guillaume Hobam 🌪️⚡ (@Chasseur_Orages) June 22, 2021

This summer, the Aisne and Oise départements in northern France have been particularly hard hit by heavy rain, with France officially recognising a natural disaster in dozens of towns and villages following flooding in July. The Grand Est region was also badly affected.

Localised flooding

Vimeux offers the example of the regular épisodes cévenols (Cévennes episodes) in the south of France at the end of summer, “where the Mediterranean Sea is very warm so the water evaporates easily and accumulates in the atmosphere, and when there is atmospheric circulation which brings this water in towards the land, and the Cévennes mountain range, this air cools down and a lot of water falls.”

According to the climatologist, these episodes could become more extreme in the decades to come, with up to 20 percent more rain over a number of hours or over the course of a day, while the summer in general will be drier than it is now.

IN PICTURES: French town hit by freak June hailstorm

Which would not be good news for French farmers: “Intense rain is not always very useful for agriculture, because it doesn’t have the time to seep in, it often runs off, especially if it falls on dry ground. So short and intense spells of rain are not necessarily what is going to save agriculture in a context of drought.”

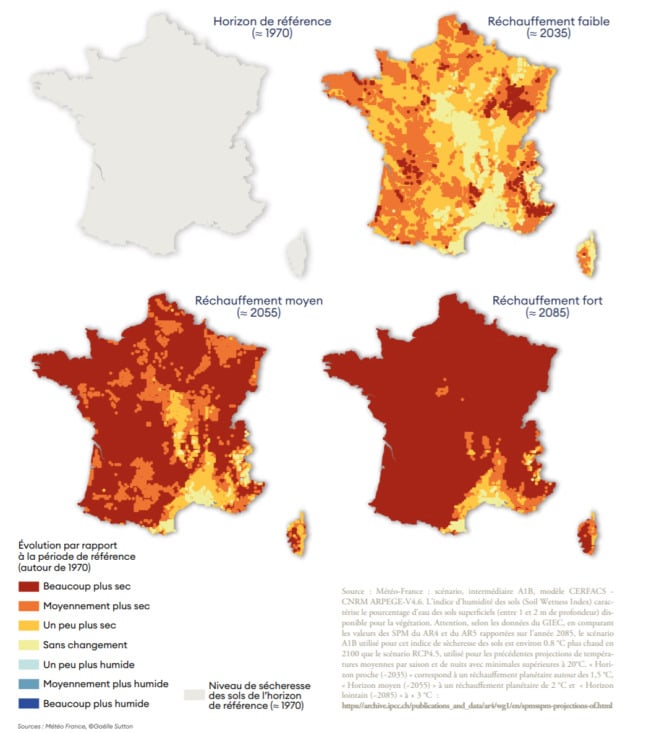

A recent report from France’s High Council on Climate showed that the soil could be “much drier” across almost the entire country by 2055, compared to 1970.

Image: Haut Conseil pour le climat. Yellow areas represent no change from 1970, light orange means the soil will be “slightly drier”, dark orange means “moderately drier”, and red areas will be “much drier”.

On the other hand, Vimeux added, “Projections show that we should have a bit more rain in the winter, but winter rains in France are not storms, but rather rain that falls slowly, allowing us to feed the groundwater tables, so that’s a good thing.”

Multiple dangers

Rising sea levels could also lead to a greater risk of flooding in years to come, particularly along the Atlantic coast. “When there is a storm, the low pressure system means there’s a slight rise in sea levels. Of course, if in a century’s time the sea is already one meter higher, a very small storm would do as much damage as a large storm today.” Vimeux cites the case of Storm Xynthia in 2010, “which brought about a rise of 1.6 metres at La Rochelle”.

READ ALSO French winemakers count cost of ‘worst freeze in decades’

The kind of storms we’ve seen this year aren’t the only danger to France’s climate – the mainland is also vulnerable to heatwaves.

“We really are an area which can be subject to heatwaves in the summer which will be more frequent, longer, more intense, and we even know that they could arrive earlier in the summer and also slightly later.”

The south of France is particularly vulnerable as well as large cities, according to Vimeux. “Certain cities are not at all adapted for us to feel comfortable during heatwaves, because there’s no greenery, there are lots of surfaces which absorb heat, like concrete and stone.”

Record temperatures

We have already seen the first consequences of this warming. The south of France experienced record temperatures in 2019, with more than 46C recorded in the Hérault département.

“It’s possible that by 2050, we will, over the course of a day or a few hours, reach the famous, mythical temperature of 50C during a heatwave,” Vimeux added. Earlier this week Sicily recorded a temperature of 48.8C.

“There are also areas which are becoming more vulnerable to fires, whereas they weren’t before, like central France.”

But is all of this inevitable?

“Our climate is more or less determined until 2050 because of human activities and the greenhouse gases we’ve already put into the air. But we can still act on the climate for the second half of the 21st century,” Vimeux said.

While certain changes could be “mitigated”, others are much more difficult to stop. “Oceans are a very slow component of climate change, and even if we stopped all of our greenhouse gas emissions today, sea levels would continue to rise over several centuries.”

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

For those living in Bretagne, this is a slightly more focused report on what we can expect in this region:

https://www.meteo.bzh/actualite/giec-pourquoi-le-climat-ne-sera-pas-plus-privilegie-qu-ailleurs-2021-08-12