Primary schools will reopen after the Easter holidays, while the rules in the Lazio region will be relaxed from Tuesday.

Meanwhile the regions of Tuscany and Valle D’Aosta will go into a form of lockdown from Monday, after hitting the threshold for new cases that automatically makes them Covid-19 “red zones”.

EXPLAINED:

Current coronavirus curbs, which vary from region to region, expire on April 6th, but all of Italy will be made a restricted red zone under maximum restrictions during the April 3rd-5th weekend.

Lazio, which has been red for the past two weeks, will move into orange from Tuesday, March 30th, before passing back into red over next weekend.

It is expected to be the only region where rules are relaxed before Easter, based on the latest weekly health data released by Italy’s Higher Health Institute (ISS) on Friday.

Two more regions that are currently orange, Tuscany and Valle D’Aosta, will become red from Monday, March 29th, while all others are expected to remain as they are now.

That leaves the updated regional classification as follows:

- Red zones: Campania, Emilia Romagna, Friuli Venezia Giulia, Lombardy, Marche, Piedmont, Puglia, autonomous province of Trento, Tuscany, Valle D’Aosta, Veneto.

- Orange zones: Abruzzo, Basilicata, autonomous province of Bolzano, Calabria, Lazio, Liguria, Molise, Sicily, Sardinia, Umbria.

There are no yellow or white zones under the latest classification.

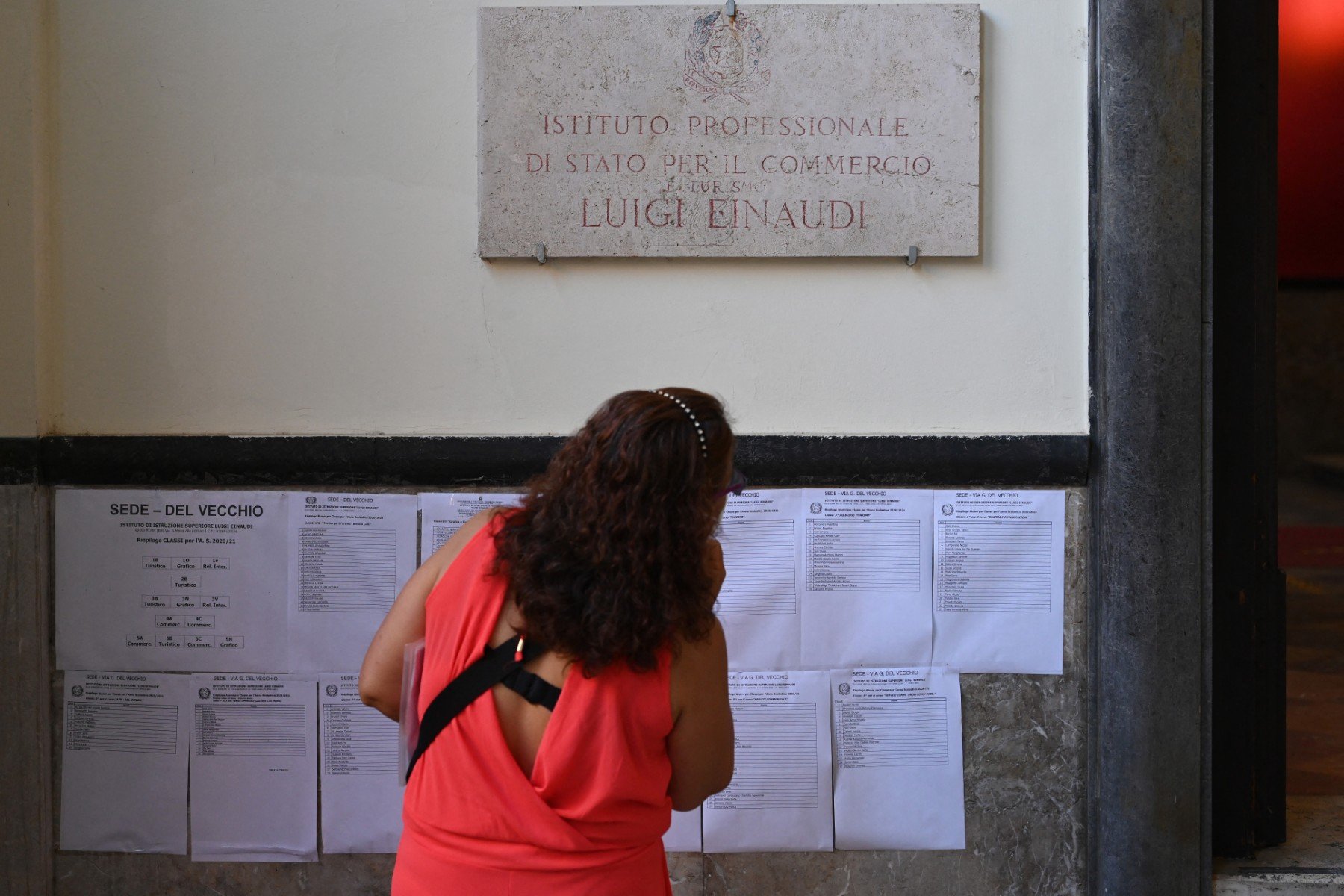

“I can confirm the decision … to open [schools] until the sixth grade,” Prime Minister Mario Draghi said during a news conference. Classes for the lower grades will be allowed to reopen country-wide, even in higher-risk regions still classified as red.

Schools were closed in most of Italy on March 15th, after the government introduced a partial shutdown to contain a third wave of infections fuelled by virus variants. The closures triggered a string of protests by students, parents and some teachers, with demonstrations in more than 60 cities on Friday.

Over the past 13 months, Italian students have had to put up with longer suspensions of face-to-face schooling than most of their peers in Europe.

Italy was the first country in Europe to face the full force of the coronavirus pandemic, and has so far reported more than 106,000 Covid-19-related deaths.

Health Minister Roberto Speranza said on Friday there were now “very early signs of a slowdown” in infection rates, allowing for some cautious re-openings.

The R rate, which measures how fast the virus is spreading, has fallen to 1.08 nationally, from 1.16 last week, said Speranza, who spoke alongside Draghi. Furthermore, the weekly number of infections per 100,000 residents has fallen under the critical level of 250, the minister added.

Speranza said he would relax coronavirus restrictions in the Lazio region, which includes Rome, moving it from red to orange category, effective from Tuesday. This will allow the resumption of face-to-face classes for students up to grade eight, and a relaxation of stay-at-home rules.

In orange zones people are free to move within their own municipalities, though bars, restaurants and museums remain shut.

In red zones all movement is limited, with only ‘essential’ shops open and socializing banned.

The Italian government has not yet announced what will replace the current rules after April 6th, but is expected to continue revising them based on the latest health data.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments