- Malmö releases first results from city-wide ‘Stop Shooting’ campaign

- Twenty criminals sign up for Malmö anti-gang programme

- Malmö calls gang suspects to meeting in hope to stop shootings

SHOOTING

Malmö pushes ahead with US anti-gang method after shootings

The recent spate of explosions and shootings in Malmö has not knocked the local police's pioneering anti-gang project off course, local police chief Stefan Sintéus said on Wednesday.

Published: 13 November 2019 20:36 CET

Ten representatives of the agencies involved in Sluta Skjut gave a press conference on Wednesday. Photo: Johan Nilsson/TT

Under the city's Sluta Skjut (Stop Shooting) scheme, nine known gang members were on Tuesday forced to attend a meeting where they were confronted by police, nurses, bereaved parents, social workers and others, all of whom sought to convince them to leave their criminal lives.

Sintèus told a press conference that he was worried that the fatal shooting of Jaffar, a 15-year-old boy, on Saturday night in a pizzeria near Malmö's Möllevånstorget square, would change the dynamic of the so-called 'call-in'.

“I can honestly say that I was worried before this call-in,” he said. “I would like to say that this was a call-in where we could tell with all of them that it sunk in.”

The nine men had all been sentenced for various crimes, and had to attend the meeting as part of their probation. Three of those invited chose not to come, thereby risking a 15-day prison sentence.

READ ALSO:

The meeting was the third since the Sluta Skjut project began last year. The project uses the Group Violence Intervention technique developed by Professor David Kennedy, who leads the National Network for Safe Communities (NNSC) at John Jay College in New York.

NNSC claims that the technique cut youth homicide in Boston by 63 percent and the number of shootings by 27 percent when it was launched there in the 1990s.

The police briefly uploaded a video of a rehearsal involved carried out before the event took place on Tuesday but later took it down. The Sydsvenskan newspaper published a clip on its website (In Swedish).

The video shows Dejan, from the local probation services; Sedat Arif, a Malmö city councillor from Macedonia who explained his tough upbringing in Rosengård, Anna Kosztovics, who leads the unit helping gang members leave crime, and Ebba, a deacon from the Swedish church, as well as two police officers and Ola Sjöstrand, Malmö's chief prosecutor.

Boel Håkansson, with the Swedish police's national unit NOA, said that so far 30 young men had shown interest in leaving criminal life. “That's one result of the work in Sluta Skjut, but we have a lot more to do,” she said.

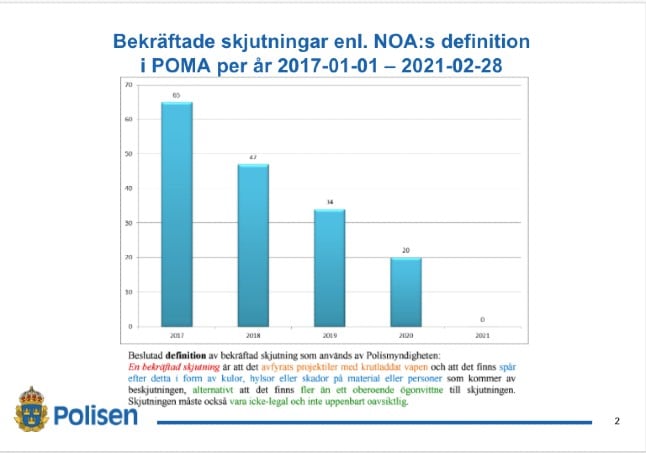

She also stressed that, even after the shootings last Saturday and on Monday, the number of fatal shootings since the project began was still down dramatically on 2018.

At Tuesday's meeting, the nine young men were lectured by Lizette Vargas, a nurse who has helped treat some of those admitted to Malmö University Hospital with bullet wounds.

“I told them what it looks like when someone comes into the accident and emergency department with bullet wounds,” she said at the press conference, according to the Sydsvenskan newspaper. “I explained how we in our profession feel when we look after a trauma patient and handle their friends and relatives.”

She said that she felt the men had been affected by what she said. “They became upset. We had made contact when our eyes met. You can tell it's sinking in.”

At the meeting on Tuesday there were more than 70 people, including representatives of sports clubs, religious organisations, and the local city government, all of whom offered various services to help the men leave criminal life.

A mother, whose adult son had died of an illness, told the men what it was like to lose a child.

But as well as the soft sell, there was a harder message.

“We are not going to accept that either you, or those you hang about with, use guns or violence,” Sintéus told them. “If you choose to continue doing that nonetheless, the police and other authorities are going to have a minute focus on everyone in the most violent group.”

Under Group Violence Intervention, police put the lives of those deemed to still be engaged in violent crime under the microscope, carrying out frequent spot checks on them.

“We know who you are and who you hang out with,” added Glen Sjögren, who has worked for Malmö police for 40 years. “We do not want more young kids to end their lives in a pool of blood.”

Url copied to clipboard!

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Well intentioned but naive approach. A multi-pronged approach is needed especially in the prisons where a great deal of indoctrination takes place. If I’m reading between the lines and many of these young people have muslim roots, I can attest to the indoctrination that occurs in the Saudi funded/wahaabi mosques and madrases. Good luck with that. It’s a tight knit gang system and very difficult to change. I only see the gang problem growing.

Malmö needs a zero tolerance policing policy.

From seemingly innocuous acts like people driving up onto sidewalks and parking their cars there while they do whatever in stores to kids openly hassling passers by to buy cocaine. The street where the shooting took place has become an open “pusher street” a d it’s happened really fast.

When the police and society turn a blind eye to the small things it’s no wonder the window of acceptable behaviour shifts.

But zero tolerance policing must also be reinforced with zero tolerance judicial decision making.

There isn’t any point arresting somebody for a serious crime if the Swedish courts won’t act. There need to be penalties which deter crime. There needs to be a process in place which identifies and then seizes the assets of crime.

Driving round in a fancy car with no visible means of financial support and having paid no taxes ever? This stuff is easy to identify! Investigate, Seize the assets. Deport. These are all tools which the Swedish state seem unwilling or unable to employ. Meanwhile cities like Malmö descend into anarchy.