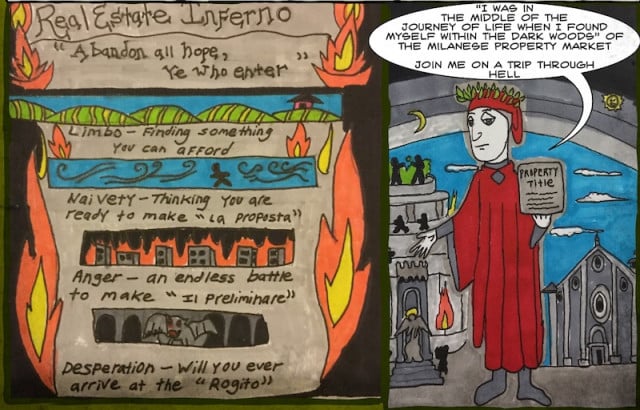

I was well aware that buying a house in Italy wouldn’t be easy. After all, I’d had plenty of warning from our contributors here at The Local – the most amusing (and also brutally honest) of which came in cartoon form – and I like to think I’ve done my homework.

So when we began the process of buying a house in a familiar place – my husband’s hometown in the southern region of Puglia – overall I thought I knew, more or less, what to expect.

But it turns out that there are some problems so strange, and so peculiar to the Italian property market, that few people could have seen them coming.

“There’s an issue with the paperwork,” frowned the woman at the bank, after I’d finally forced someone to look at our mortgage application – a mere two months after we’d rushed across the country in a heatwave to submit it.

Of course there is, I thought. When is there ever not? I mentally calculated whether we had time to go back to the town hall for a third time that day, to correct a spelling mistake or replace yet another lost form.

But she was still shaking her head, and tapping at the plans of the house with a startlingly long, red fingernail.

“The people selling the house don’t technically own this part,” she said, pointing to a grey square that represented our tiny upstairs bathroom.

I just shook my head in confusion. How can they be selling something they don’t own?

Italy’s Puglia region is famous for many things, but efficiency is not one of them. Photo: Depositphotos

She was telling me that the next-door neighbours had given the owners that room (which shares a wall with the house next door) “as a gift”.

In Italy it’s possible to transfer property ownership as a ‘donazione‘ for various reasons. In this case, it was likely done in order to avoid the comune admin fees involved in a sale – as they would no doubt cost far more than the miniscule piece of property itself was worth.

But a donazione isn’t as simple as just giving part of your property away. Under Italian law, this actually means the next-door neighbours still, technically, own our bathroom for another twenty years from the date they ‘donated’ it, and also have the right to change their minds and ask for it back at any time.

“So who’s the owner, then?”

She cleared her throat, and slowly began reading out a long list of names, complete with dates of birth, and sometimes, death.

I counted them on my fingers, and I’d run out of fingers by the time she stopped reading.

“Ten people?” I accidentally shouted. “How can they all own my bathroom?”

The property was in the name of a now-deceased woman and her nine adult children. The oldest daughter, a Signora M, still lived in the house next door, and techically she owned the largest share of the bathroom – ten twenty-sevenths of it, to be precise.

I tried to visualise what ten twenty-sevenths of such a small room would even look like, and exactly how many bathroom tiles Signora M would be the proud, theoretical owner of.

Under Italian law, a property is automatically divided between the owners’ children if said owner dies without leaving it to anyone in particular. In Italy, houses are very often passed on and inherited this way

So you can end up with an apparently not-that-unusual situation in which, over a few generations, old houses are carved up into countless shares – which can lead to whole families bickering over who gets to live there. And, as I was finding out, problems when trying to sell.

“So if any of these people decide they want access to their property…?”

“Legally you will have to provide access,” she nodded.

A vision of this unknown family of ten tramping up and down my stairs to use the loo flashed through my mind. Could I put them all on a bathroom cleaning rota? It wasn’t clear.

I was brought down to earth with a bump at that point as she hammered home what this meant for us now in practical terms: yet another expense.

“Legally if any of them decide they want it back, you’ll lose the property, which is why the bank will require extra insurance.”

I think I died a little inside at that point. More insurance, after we’d already agreed to fork out for home insurance and life insurance, a requirement of the bank.

I’d been told by numerous experts to expect the cost of additional fees related to buying a house to be around ten percent of the property price, but thanks to all the additional insurance on a house that wasn’t worth much to start with, we’d sailed past that figure long ago.

READ ALSO: Italian problems: Figuring out the post office (and how to get through the door)

And it was especially frustrating since all of this was really just a technicality.

Some notary had, most likely, put all these names down on the property title when our bathroom was handed over as a ‘gift’ – no doubt because the house next door is probably also split between the whole family.

There’s a high chance that these people named on the title either had zero interest in our poky bathroom, or didn’t even know any of this had happened.

But this didn’t make our extra insurance cost any less: the bank quoted us almost a thousand euros for the policy.

And in fact, this was only one of a long list of problems we discovered with the paperwork on the house – thanks to the bank or the notary – that the agency hadn’t mentioned.

READ ALSO:

- What’s wrong with the Italian property market?

- Property: What can you buy for 500K around Italy?

- The real cost of buying a house in Italy as a foreigner

It took a series of tense meetings with the seller and estate agent, not to mention me threatening to tear up the compromesso and cancel the whole thing (as we would be legally entitled to do at that point), before the seller agreed to cover the cost of the extra insurance on the house.

But our problem wasn’t solved.

The final and most thorough check of the paperwork by our notary revealed that this and oher issues we’d previously been told (by our agent and another notary) were “not a problem” were actually such a big problem that she blocked the sale until they could be resolved.

In the UK you’d probably have all the paperwork thoroughly checked over and get a survey done before even making an offer on a house. In Italy – at least in Puglia – this isn’t the way things are usually done. This strikes me as odd since, with old houses like this, it’s pretty rare for the paperwork to actually be in order.

We did have a survey carried out and the documentation looked at by a notary before we agreed to buy the house, and we’d even obtained a signed declaration from the agency stating that there were “no issues” with the property or its ownership.

Obviously, that was useless – this discrepancy among others was never flagged up, or was deemed inconsequential. (I wasn’t too shocked to later find out that the first notary we went to was a good friend of the estate agent.)

As I found, it doesn’t matter how well-prepared you think you are, there’s always going to be something.

“Expect the unexpected” remains the number one rule when living in Italy – and especially, it seems, when you’re trying to buy a house.

Tales of property hell abound in Italy, from Milan to Bari. Image: Adam Rugnetta

Have you experienced a property-related nightmare of your own in Italy? We’d love to hear your story. Get in touch here.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments