More than 40 percent of east Germans believe freedom of speech has deteriorated or hardly changed at all since the days of the communist GDR (German Democratic Republic).

That’s the result of a representative study commissioned by Zeit newspaper and carried out by the Berlin Institute of Policy Matters.

The research aims to highlight how eastern Germans feel about reunification, three decades after the Berlin Wall fell.

“All in all the mood is bad,” said Zeit in their article about the findings of the study.

“Something is going wrong. 30 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, disillusionment and disappointment prevails in the east of the country.”

READ ALSO: 10 things you never knew about German reunification

The study, which involved interviewing 1,029 people in the five eastern German states and in Berlin, found a widespread feeling of scepticism about how Germany has developed since 1989.

The Berlin Wall opened on November 9th, 1989, after months of unrest and peaceful demonstrations. It ended 28 years of division between the GDR and West Germany.

It paved the way for reunification which took place officially on October 3rd, 1990. Germans receive a national holiday on the Day of Unity.

But studies over the years show there are still problems bubbling beneath the surface.

This can also be seen in the way many eastern Germans in particular are turning away from mainstream parties and looking to anti-establishment groups, such as the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD).

Under-appreciated

Zeit found a clear majority of respondents – 58 percent – feel they are not better protected from state arbitrariness today compared to the days of East Germany.

The study also found less than half of eastern Germans (48 percent) believe that democracy in Germany works well.

There appears to be a strong feeling that eastern Germans are under-appreciated.

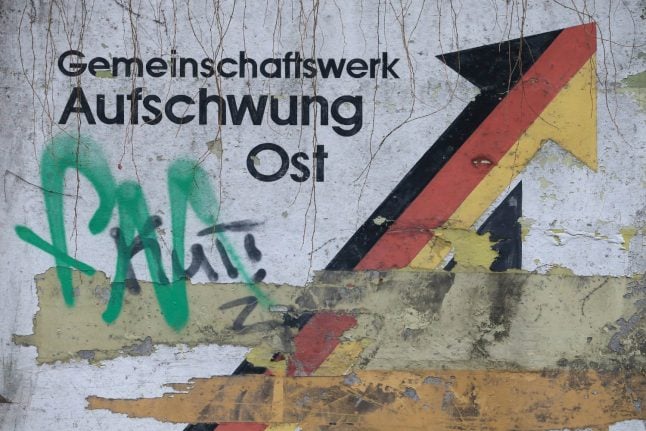

A sign in Wolmirstadt, Saxony-Anhalt. Photo: DPA

A sign in Wolmirstadt, Saxony-Anhalt. Photo: DPA

A huge 80 percent of respondents say the west has not sufficiently appreciated the east's achievements since reunification – and that’s including younger east Germans, who did not experience the 1990s themselves.

A total of 61 percent of eastern Germans say leadership positions in business are too rarely occupied by people from the east, and 56 percent are dissatisfied with what they perceive as a low number of federal authorities based in the east.

Yet 54 percent of eastern Germans said the standard of living had improved since the days of the GDR, indicating that many parts of life have improved.

When comparing the 2019 results with a study Zeit commissioned in 2000, however, the negative mood is clearly getting worse.

In 2000, 67 percent of eastern Germans said their hopes of reunification had largely been fulfilled; in 2019, that figure has dropped to 52 percent.

Whereas in 2000, 74 percent said that freedom of expression had improved compared to the GDR era, in 2019 it was only 59 percent. Satisfaction with school education and social justice has fallen, as has the number of of those who “feel comfortable in society” (only 26 percent say they feel more comfortable than in GDR times).

READ ALSO: Talkin' bout my Generation: What unity means to eastern Germans

“These are numbers that are hard to grasp at first glance,” writes Zeit.

“The reprisals, the Stasi, the Wall – has all been forgotten? Has the memory of the dictatorship's injustice really faded that much?”

However, experts point out that the closure of East Germany-based firms after the fall of the Wall, the loss of jobs and financial security felt like a betrayal to many people in the east, contributing to a feeling of insecurity.

And Germany has been going through a hugely turbulent political time.

Chancellor Angela Merkel’s decision to keep borders open in Germany during the height of refugee crisis in 2015, “without any restrictions, uncontrolled and without debate and a vote in the Bundestag has been perceived by many people as arbitrary state action – and the influx of hundreds of thousands of refugees increasingly as a threat,” said Richard Hilmer, head of Policy Matters and the ZEIT study.

“And not only in the east,” he added.

Meanwhile, for many citizens life in the GDR was fulfilling. Zeit points out that for lots of eastern Germans, the Stati is not the first thing that comes to mind when they think of their former country.

However, it should be noted that the age of eastern Germans does play a role. The younger the respondents, the more critical their attitude towards the GDR tends to be.

Eastern Germans' voices not being heard

The study illuminates that eastern Germans are frustrated, believing their voice isn't heard, and they feel they don’t get to play a role in shaping Germany.

A total of 70 percent said they are unhappy that too little “consideration is given to the opinion of the people in east Germany”.

READ ALSO: 'The wounds still hurt today' despite progress: 28 years of German unity

There are some issues where dissatisfaction is particularly strong: 67 percent of east Germans are unhappy with the development of unequal wages in the east and west, while 68 percent are dissatisfied with pensions.

Meanwhile, 83 percent of those questioned are in favour of an ‘eastern quota’ for managerial positions in the business sector and 82 percent would like to see that quota in politics to increase representation.

According to a study by the University of Leipzig, less than five percent of managers in politics, business, law and science in Germany as a whole come from eastern states.

Sociologist Raj Kollmorgen believes the situation could be transformed with policies, but that eastern Germans can also do something about their situation by not seeing themselves as victims.

“We east Germans must not see democracy only as a service enterprise that solves problems and fulfils desires,” he said.

Instead, Kollmorgen said, eastern Germans must enter (political) parties, found associations, use the possibilities of freedom and democratic participation for themselves. “The east Germans”, he says, “have to shake the power relations themselves.”

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments