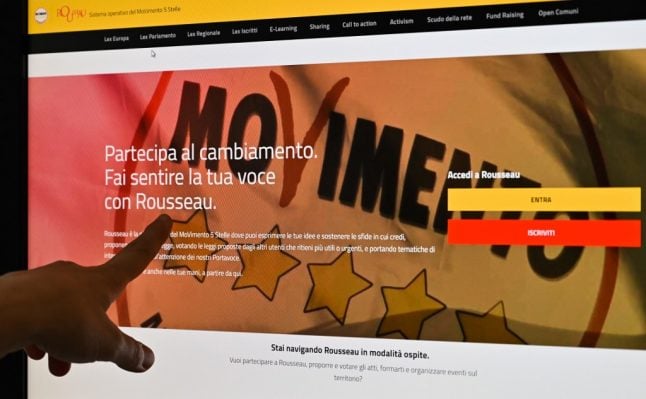

Named after the 18th-century French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, it is supposed to empower ordinary citizens and guarantee transparency, but critics have condemned it as secretive and vulnerable to cyber attacks.

100,000 members

Launched in 2016, it currently has some 100,000 members, M5S chief Luigi Di Maio said in July. But critics have lamented a lack of official documentation or certification from a third party to attest that this figure is correct.

READ ALSO: An introductory guide to the Italian political system

The M5S's blog says the number of people registered on Rousseau rose from 135,000 in October 2016 to nearly 150,000 in August 2017, before dropping to 100,000 a year later.

But political analysts say it cannot be seen as representative of M5S supporters, as the membership numbers are a drop in the ocean compared to the 10.7 million Italians who voted for M5S in the 2018 general election.

How does it work?

Members are called on to vote on M5S programmes or candidates, with the online consultations often returning large majorities and highly anticipated results.

Critics say there is no transparency as to who has voted or how, with M5S only very rarely using third parties to certify its digital ballots are in order, leaving room for allegations of voting fraud.

The M5S says the database keeps a history of all individual electronic votes as there are no secret ballots.

Who started it?

The platform is managed by Davide Casaleggio, whose father Gianroberto founded the Movement along with comedian Beppe Grillo.

Critics say the Casaleggio family has been pulling political strings from behind the scenes from the start.

ANAlYSIS: How the rebel Five Star Movement joined Italy's establishment

Photo: Filippo Monteforte/AFP

What about hackers?

Rousseau insists user details are safe — but has suffered several hacker attacks in the past. In 2017, a 26-year-old student hacked the platform several times and published the names of members and donors and their payment, password and contact details.

That leak caught the eye of Italy's Data Protection Authority, which in January 2018 — in the run-up to the general election — said the platform was using an outdated content management system that was vulnerable to cyber attacks.

TIMELINE: How did Italian politics get to where it is today?

But in September 2018, another hacker struck, publishing the emails, passwords and phone numbers of three ministers, including those of Di Maio, who holds the post of deputy prime minister in the outgoing coalition.

In April, the Data Protection Authority noted “significant improvements” in the platform's security, but slapped the company with a 50,000-euro fine for failing to fix all the flaws.

And what about money?

The M5S's lawmakers — 226 in the lower house of parliament and 112 in the upper house — are obliged to shell out 300 euros a month each for the platform's upkeep. Their contributions bring in some 1.2 million euros yearly for the Casaleggio group.

Some have complained over the lack of accountability on where the money goes, with several being ticked off publicly for attempting to wriggle out of the mandatory payment.

By AFP's Franck Iovene

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments