Adolf HItler's 'political testament', first published on the July 18th, 1925, was directly borne out of the Nazi leader's imprisonment in Landsberg Prison. It followed the failed 'Beer Hall Putsch' – or Hitler's attempt to seize Munich and use it as a base of power in a fight against Germany's Weimar Republic Government – of November 8th, 1925.

Arrested shortly afterwards for treason, he was sentenced to five years in prison, at Landsberg Prison, west of Munich. In actuality he'd serve less than a year.

The main entrance to the Landsberg prison, as seen in 2014. Photo: DPA

In Landsberg, Hitler would come to the realization that the most effective means by which to achieve power was not by force, but by the ballot box. Thus, with not much to do except grow a belly (contemporary sources describe the food as rather plentiful), Hitler began dictating his vision for Germany. This was typed up by fellow prisoners Emil Maurice and Rudolf Hess, who were both jailed with Hitler following 'the Putsch'.

Both of Hitler's 'stenographers' would sit at a typewriter in Hitler's cell, as the Führer-to-be lectured on history, racial theory and geopolitics – often in a grandiose, dramatic fashion. Some have speculated that Maurice and Hess heavily edited Hitler's words to improve readability and clarity, and dictation sessions could last several hours.

Within the book, much of Hitler's dark dream for Germany is outlined. 'Lebensraum', or living space' is a recurrent theme, calling for Germany to subjugate its eastern neighbours in order to give the German 'Volk' room to prosper. His virulent Antisemitism is also brought to the fore, describing the deleterious effect he thought the Jews had on Germany numerous times.

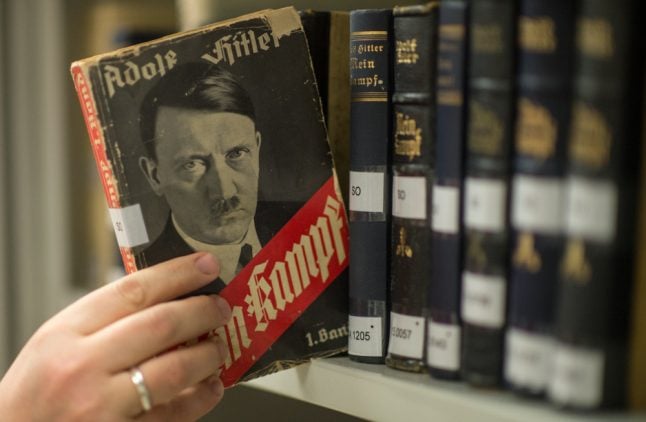

Originally sold in two volumes and published by Ever Verlag – the Nazi Party's own publishing house, the book sold modestly initially, mostly to Party members over the second half of the 1920s. It was only once the Nazi Party gained power in 1933 that sales approached anything near a 'bestseller'.

In addition to the sales it made following Hitler's rose to power, the Nazi state otherwise ensured that nearly everybody had a copy – given to them at school, when they married, or when they joined the armed forces. It was hard to avoid during the years of Nazi rule.

Documents from Hitler's prison stay were auctioned in 2010. The picture shows (L-R) a letter to a car dealership, a visitor card and a document confirming Hitler's admittance as a prisoner at Landsberg. Photo: DPA

Following the war, publication of the book was suppressed for over 70 years, only lifted in 2016 – and only then in a heavily annotated edition that fact-checks Hitler's claims. Even then, there was an outcry in many sections of German society.

SEE ALSO: Hitler's 'Mein Kampf' becomes German bestseller, year after reprint

In my opinion, they needn't have bothered. It's when Hitler's words are printed on the page that they lose much of the power they had during his speeches. In fact, given room and space to breathe, most of his prose comes off as the hyperbolic, hateful nonsense it is.

Put it this way – the book's original title was supposed to be 'Four and a Half Years (of Struggle) Against Lies, Stupidity and Cowardice'. If that doesn't give you an idea of the kind of pompous, half-baked material we're working with here, nothing will!

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments