Leah Pattem’s recent article about Madrid’s anti-homeless architecture has caused quite a stir.

We heard claims that “homelessness is a choice”, that “most homeless people have substance abuse problems”, and that “shelters are safer than the streets”. But there was one person who came forward speaking of his own experiences, and it’s not always as expected.

Here’s Andrew’s story:

“My name’s Andrew Craig. I’m a Yorkshire lad, 36 years old. I suppose my story starts at the age of five when I was taken into care because both of my parents were ill – my Dad had MS and suffered various other difficulties as a result of having been in the army, and my mother had a heart condition and epilepsy.

By the age of 13, I’d lost both of my parents and was an orphan. For a couple of years, I was put into various foster homes, and due to this, school was a struggle. I was eventually placed in a children’s home, but there was abuse of various kinds and so I’d run away quite often and slept rough.

At 16, I started an apprenticeship with the army. I got my A-levels and an engineering degree, and toured Iraq and Afghanistan. After 12 years, I’d developed Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, which the army didn’t seem to acknowledge, perhaps because it hadn’t manifested itself too badly at that point. PTSD did ultimately leave me poorly equipped to deal with a work accident, which I can imagine other people wouldn’t have struggled with as much. At the same time, unfortunately, the breakup of a relationship I was in left me without a place to live, and that’s when I ended up homeless for the first time.

I went to Manchester with the plan to sleep on the city streets, thinking that it would be safer because of the city’s more complex architecture (meaning more places to shelter), and possibly more access to help, but I was naïve. I stayed in a hostel for one night, but it was very scary. It was noisy throughout the night, and the lock on my door didn’t work. The sheets on the bed were clean, but I could smell the mattress really badly, so I slept on the floor in my sleeping bag.

I didn’t feel safe: there were a lot of people who suffered substance abuse and had serious behavioural issues. There were cameras but only one warden, who I never saw. I saw fights, drug taking and even drug dealing.

In the morning, I got a knock on my door, “Up! Out!” they shouted. I remember at the time thinking that prison would be friendly, safer and cleaner, but then I wouldn’t know who my neighbours were going to be. Even though I’m sure that other homeless shelters couldn’t possibly be this bad, that night was enough for me to never want to go back.

I reached out to a few friends, but most of them weren’t keen to give me the help I really needed, and so I continued sleeping rough on the streets of Manchester. I was urinated on a few times while sleeping and beaten up so badly by a group of thugs that I ended up in hospital. I’d been inside my sleeping bag, so I couldn’t get up and run away.

After that, I decided to leave Manchester and I moved to Buxton – it’s a beautiful spa town, and that’s where I met a good friend of mine, Dave, who took me under his wing. He had also been in the army and was living rough too, so we both lived in the woods together. It was tough but much easier than living in Manchester.

After around a year and a half of sleeping in the woods, someone set fire to Dave’s sleeping bag while he was inside it. He was taken to hospital and underwent numerous operations to repair the skin all over his legs where the plastic had melted to him.

Fortunately for Dave, after coming out of hospital, he was moved into a council flat. The guy who set him on fire did two years in prison and now lives in the same council housing complex as Dave.

This incident made me realise that being homeless was just too dangerous. I managed to get a job while sleeping rough – it was just one day a week but was enough for me to eventually save up a deposit and rent a room. I never begged – I was probably too proud after being in the army, remembering being in my uniform and being a part of something important, but then suddenly finding myself in a position of needing charity. I just couldn’t do it – I couldn’t even ask for help.

I’ve now completed a degree in counselling and psychotherapy, and that’s when I met a Spanish lady who I fell head over heals for. We moved to Spain together, end even though it didn’t work out, she still feels like my family. And I love Spain – the people, the country, the weather. I now live between the UK and Spain, spending around half the year here in Madrid.

I’m currently setting up my own counselling practise. My main motivation is helping people get off the streets. Having been there myself, I know it’s possible, even when it doesn’t seem like there’s a way out.

Once upon a time, I thought that homeless people were alcoholics or drug addicts, but I was never either of those things. Most people were quite hostile towards me when I was homeless – they and my ‘friends’ just didn’t seem to want to know. However, every now and then, someone stopped to talk to me. Just 15 minutes of conversation with someone made me feel like I was part of the human race, and that I hadn’t fallen through the cracks and completely disappeared. There were times when I wanted to end it all, but just those conversations gave me a spark of hope and kept me going through my hardest moments on the streets.

I was homeless for two years, but it felt like a lifetime, and the trauma and fear of being homeless will never leave me. Even now, I think I should swap my car for a van and buy a good sleeping bag, so that if I end up homeless again, I still have somewhere to sleep.

I’m hoping to move to Spain full time one day and work with homeless people here, but I don’t know if Brexit will affect this. I guess I’ll just have to wait and see.”

A bench with armrests to deter homeless people sleeping. Photo by Leah Pattem.

We often talk about the good things that bring us to Spain, but we don’t often talk about the good things that we bring to Spain. In Andrew Craig’s case, love brought him here, but what he brings with him is a plan to help vulnerable expats, and there are many.

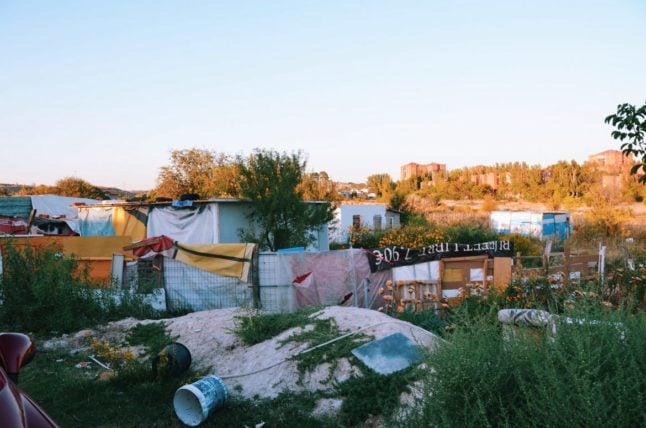

After the financial crisis, many British expats suddenly found themselves without a home. The catalyst was often the loss of work, therefore loss of income and, ultimately, the loss of a rented property. Thousands of homeowners too became victims of unlicensed housing that had been illegally built during the pre-crisis boom. They watched their houses razed to the ground – life savings gone.

Seeking help can be hard for many reasons, including not being able to speak the local language. When the government doesn’t help, charities often step in, but, as Andrew found, offering just food and shelter does something, but what so many need is inspiration, and that’s where Homeless Entrepreneurs comes in.

Barcelona-based social enterprise, Homeless Entrepreneurs works with homeless people at every stage of their recovery: from that initial 15-minute conversation to training, finding a home and setting up a business.

Homeless Entrepreneurs is a non-religious organisation, and purposely avoids any kind of short-term fixes. Those who make a full recovery with them then have the opportunity to help others get off the streets too.

“One of my biggest barriers when I was homeless was confidence and self-worth, so to have someone who believes in you and encourages you to get where you want to be is invaluable”, said Andrew.

A 15-minute conversation gives someone a voice. It empowers them and also enlightens us. Nothing is going to change overnight, but some of us are working on it – and you can too.

Learn more about the life-changing work of Barcelona’s Homeless Entrepreneurs here.

IN PICS: Madrid's hostile anti-homeless architecture that you see everyday but don't even notice

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.