Sweden has been preparing for its 2018 elections for almost two years. Security institutions of this non-Nato Scandinavian country studied relevant elections abroad, and especially the ones that have been tampered with by Russia.

READ ALSO: How Sweden got ready for the election-year information war

There are at least three reasons why we have seen only limited interference activities.

First, the Swedish government was ready. It used its robust civil crisis-response experience and established an election task force composed of dozens of relevant agencies and actors in both the public and the private spheres to safeguard independent elections. Thousands of public officials were trained and the most extensive manual on countering influence operations was published.

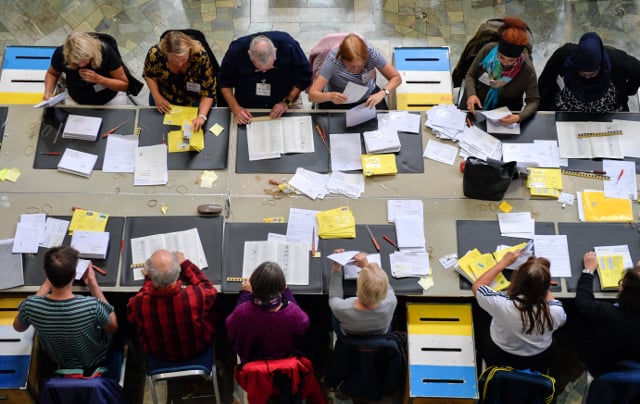

On the technical side, paper ballot electoral systems limit the fear of delegitimization of the electoral results by a cyber attack. In military terms, we would say that the target has been hardened while expecting the enemy attack.

Second, though Sweden is domestically vulnerable mainly due to real internal grievances over migration-related issues, there are local conditions which make it harder for Russian intelligence to operate. Limited Russian resources capable of communicating fluently in Swedish and a small Russian minority (fewer than 20,000) are only a start.

More importantly, Swedish political culture has made it harder for a strong pro-Kremlin political party to be cultivated. Similarly, the post-MH-17 environment made it much harder for the Dutch PVV party of Geert Wilders to openly join the Russian allies on the European far-right map.

In the country of Vikings, there is yet no counterpart of the usual Kremlin proxies, such as the French National Front, Austrian Freedom Party, or Italian 5-Star Movement. So far, Russia's political allies are limited to a new micro party (Alternative for Sweden) and individuals pushing the “neutral” agenda within the mainstream parties. The strongest anti-establishment party, Sweden Democrats, has not yet shown itself as a Kremlin proxy, as most European far-right parties are. The question remains as to how successful Russian cultivation efforts will be in the future as they are clearly the main Kremlin target.

Third, timing is important. In the Russian calculation, strategic deployment of resources is ultimately decided upon cost-effect assessment. In the same time period, three arguably more significant political games with larger impact potential are happening – US midterms, elections in deeply vulnerable Bosnia and Herzegovina and the vote in Latvia in early October.

It doesn't take a rocket scientist to see the simple game-plan, which in many cases can be politically natural and organic.

READ ALSO: Everything you need to know about the Swedish election

Russian proxy messengers across the West (like conspiracy theorist Alex Jones) have targeted Sweden due to its migration-related policies and massive bot activities have spiked in the days prior to the elections. A Swedish exit from the European Union ('Swexit') has been a recurring narrative in right-fringe communication, despite the fact that EU support in Sweden is at an all-time high. This has been repeated and enhanced by alt-right and Russian English-language media. Moreover, a rather well-coordinated delegitimization campaign against the conservative party (Moderaterna) by the youth Nazi movement was conducted. The political logic is clear – by undermining the ruling Social Democrats who are weak on migration and delegitimizing the moderate right, the far-right can only gain and future Russian cultivation efforts may potentially bear fruit.

The Russian strategy seems to be clear. Moscow probably realized that going in with direct aggressive activities would backfire due to Swedish government preparedness and it would undermine the strategic objective – keeping Sweden out of Nato. Therefore, direct interference action wasn't the main tactic – as it was for example in the 2016 US presidential elections or 2016 Brexit campaign with use of massive disinformation and political influence methods. Russia would have probably chosen a more aggressive approach if the Nato-membership question was one of the main campaign topics, but it wasn't.

The Russian playbook used in Sweden resembles the 2017 Bundestag elections in Germany. Moscow apparently expects the main targeted outcome will play out naturally. While German Social Democrats already played an important role for the Kremlin's strategy by pushing for Nord Stream 2, as a Russian tool of geopolitical blackmail, Moscow will clearly try to cultivate the far-right in Sweden as the potential future blocker of Swedish accession to Nato. For this, you don't need aggressive hack-and-leak tactics which Russia deployed against Hillary Clinton. You simply amplify the migration-related narratives and keep cultivating the far right which is already quite strong.

Jakub Janda is the Director of the Prague-based European Values think tank and Head of the Kremlin Watch Program. He has advised the Czech Interior Ministry on countering hostile foreign influence operations.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments