For decades the cities of the Rhine, foremost among them Cologne and Düsseldorf, liked to claim that their famous Karneval processions were a hotbed of anti-Nazi satire during the 1930s.

Only more recently has documentary evidence shown that the Nazis in fact used the Karneval to spread their anti-Semitic worldview by building floats depicting age-old anti-Semitic stereotypes. Many carnival associations were also taken over by the Nazis during the 1930s.

Most uncomfortably for Cologne, anti-Semitism was in fact prevalent at their carnival parade long before the Nazis came to power. Cologne Karneval association banned Jews from taking part as early as 1923, just a year after the first Jewish carnival club had been established.

This year, the Jewish community in Düsseldorf hopes to heal old wounds – and fight modern day anti-Semitism – by entering the first ever Jewish float into the city’s famous Rosenmontag parade on February 12th.

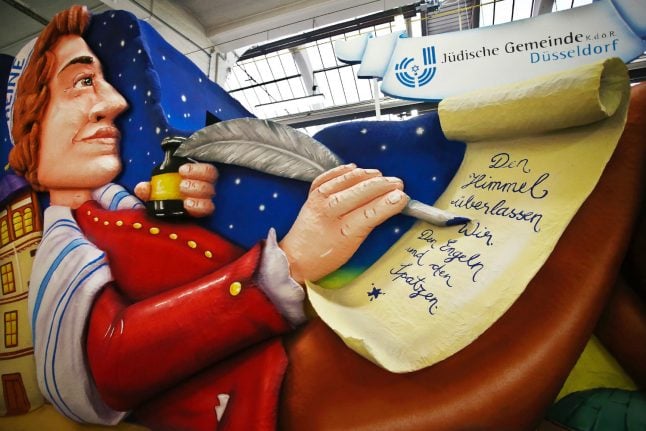

The float, which cost €35,000 to build, will depict the 19th century poet Heinrich Heine, who was born in Düsseldorf. An inscription on the side notes that “we are celebrating the greatest Jewish son of our city.”

“We live in a time in which anti-Semitism is becoming acceptable again – where it has gone from being confined to the far left and right to slowly entering the mainstream,” said Michael Szentei-Heise, head of the Jewish community in Düsseldorf. “We’re a part of Düsseldorf society – we belong here and anti-Semitism has no place here.”

Just as synagogues and other Jewish buildings are almost always guarded in Germany, the float will also have “special security arrangements,” Szentei-Heise said. But he added that these would not be outwardly visible on the float.

In Cologne, there are also signs of a mini Jewish renaissance in carnival participation. This year a Jewish group has been founded to participate in the city's Karneval, which attracts millions of visitors from across the globe.

But Szentei-Heise admits that the reactions in the Jewish community have been “very diverse.” While the Jewish community in Krefeld donated money for building the float, other communities in the region showed little understanding for the project.

For Szentei-Heise, the float is ultimately an attempt to address serious issues with a bit of humour.

“You can complain and moan all day about what you read in the papers – but you can also drive a float through the Karneval,” he says.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.