1. Saukalt

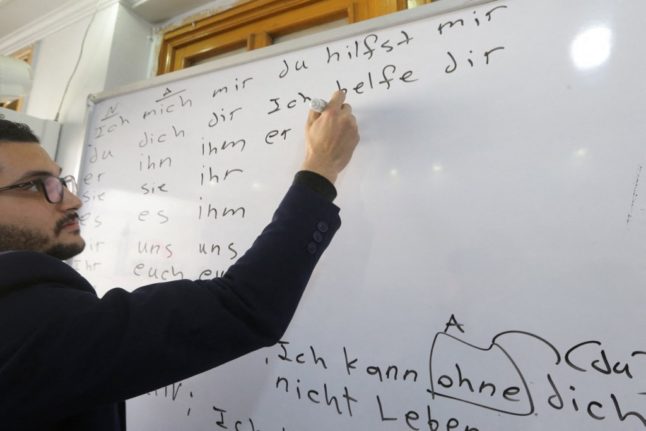

Photo: DPA

Photo: DPA

Now that it’s dropping into the sub-zero temperatures, kalt (cold) is just not going to hack it. Instead, the word you need is saukalt. Literally translating as “pig-cold” it means it’s flipping cold, and it’s the perfect description for that next step up as we head into the frozen months.

2. Naschkatze

Photo: DPA

Photo: DPA

As you’re tempted back into those Christmas markets time after time, this word may also come in handy. A Naschkatze (nibble-cat) is the term for someone with a sweet tooth, and who can blame you when there’s such a delicious selection of cakes, cookies and sweets to delve into this winter?

3. Gemütlichkeit

Photo: Pixabay

Photo: Pixabay

The colder it is outside, the warmer it feels inside, and that’s why we’re grateful for the German word Gemütlichkeit (its closest translation is “cosiness”). As you pile into a warm wood-panelled bar and wrap you’re hands around a steaming mug of Glühwein, you only need to exclaim: “So gemütlich!” No one does winter warmth better than the Germans, so make the most of the Gemütlichkeit.

SEE ALSO: Why Gemütlichkeit is the best German word for winter

4. Schneematsch

Photo: DPA

Photo: DPA

Many of you are probably hoping for some snow this winter. But the main downside of the white stuff is when it starts to melt. Yes, when it turns to slush, snow suddenly loses its magic. The German term Schneematsch (snow mud) describes that slurry of white and brown that starts to pile up on street corners and seep through your shoes.

5. Die Kuh vom Eis holen

Photo: DPA

Photo: DPA

If someone tells you “du hast die Kuh vom Eis geholt” (You’ve got the cow off the ice), they’re probably not being literal (unless you’re a dairy farmer next to a frozen lake). Instead, this rather wintry idiom really means that you’ve saved the day. If someone manages to pull something out the bag as you teeter on the edge of disaster, that’s the way to thank them.

6. Aufs Glatteis führen

Photo: DPA

Photo: DPA

Another winter-inspired idiom, aufs Glatteis führen means to “lead [someone] onto the black ice”. The English equivalent is to “lead someone up the garden path”, or to lead them astray. So next time you think you’ve clinched a great deal on that hat at a Christmas market, and then you see it for half the price in a shop window on the way home, you’ll know that the convincing vendor has led you “aufs Glatteis”.

7. Schnee von gestern

Photo: DPA

Photo: DPA

Das ist jetzt Schnee von gestern (literally “that’s yesterday’s snow now”) is best translated as “that’s water under the bridge now”. It’s a great phrase to bring out this Christmas, when it seems that an old family argument is about to kick off again. Just tell them calmly that “it’s yesterday’s snow”.

By Alexander Johnstone

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments