The Italian satirical dramatist, who died on Thursday aged 90, was banned, censored, rebuked, reviled and refused a US visa for his political affiliations.

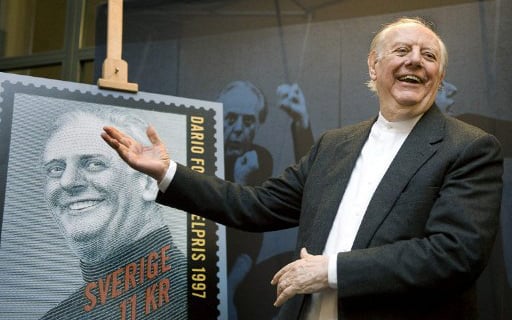

Yet he won the Nobel prize for literature in 1997 and many of his 40-odd plays were translated into dozens of languages and performed to packed houses all over the world.

Mime, stand-up comic, historian and political commentator, described by one critic as “quite possibly the world's largest performing rabbit,” Fo was a darling of the avant-garde but a thorn in the side of bureaucrats and politicians.

His agit-prop drama drew on such highbrow effects as Jacobean and miracle plays, Japanese theatre and Aristotle, not to mention the writings of Marx, Freud and other polemicists.

The eldest of three children of a railway station master and amateur actor, Fo was born on March 24th, 1926, in Sangiano, “a town of smugglers and fishermen” on the shores of Lake Maggiore in northern Italy.

In his childhood he was steeped in popular theatrical and narrative traditions – his grandfather was a well-known “fabulatore” or storyteller.

Courting controversy

After studying fine arts and architecture in Milan, he was irresistibly drawn to the theatre.

He made his debut as an actor in 1952 at Milan's Teatro Odeon and recorded a series of comic monologues for radio.

At the same time he began to write satirical cabarets and to act in the Piccolo Teatro in Milan, forming his own revue company with two friends.

Their first collaboration was an irreverent history of the world, “A Finger in the Eye”, in which the actress Franca Rame, a member of a famous theatrical family, was a member of the cast.

Fo married her in 1954 and together they founded their own company, in which she was the leading lady and Fo writer, producer, mime and actor.

Early plays were gentle satires like “Corpses Disappear and Women Strip” (1958) and “Archangels Don't Play Pinball” (1960) and “Anyone Who Robs A Foot Is Lucky In Love” (1961).

His work became more political in response to the popular uprisings and turmoil of 1968. With left-wing support he founded the cooperative theatre “Nuova Scene,” which soon however wound up because of ideological controversy.

He found a ready audience for his topical satire, epitomized by “Mistero Buffo” – a retelling of the Christian gospels in an improvised format, which allowed him to comment on everything from corruption in the Catholic church to contemporary social and political issues.

The play outraged the Vatican and was condemned by the pope at the time as “desecrating Italian religious feelings”.

'Jesters of the Middle Ages'

In 1970 Fo broke with the Communists and formed a new troupe, “La Comune”, with one of his best known works, “The Accidental Death Of An Anarchist”, opening that year.

His outspoken views and political commitment did not endear him to the authorities, and he had numerous run-ins with the Italian government and his works resulted in court cases.

Fo's 2003 play “The Two-Headed Anomaly”, which took aim at Italy's then-prime minister Silvio Berlusconi and Russian President Vladimir Putin, sold out in the theatre but was censored on television after a complaint by one of the billionaire politician's aides.

In the play, part of Putin's brain is transplanted into Berlusconi's, transforming him into a muddled, vodka-swilling Russian speaker.

Fo became increasingly engaged on the political left, running for mayor of Milan in 2006, and in recent years Fo fought for Italy's populist, anti-establishment Five Star Movement.

The Nobel jury honoured Fo for work which emulated “the jesters of the Middle Ages in scourging authority and upholding the dignity of the downtrodden”.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments