“Informing yourself about what young artists do is essential. You can’t always just look at van Delft and Rembrandt,” the 90-year-old Hannelore K. says.

Remaining true to this mantra, the elderly art enthusiast paid a visit to Nuremberg’s Neues Museum für Kunst und Design on July 13th this year.

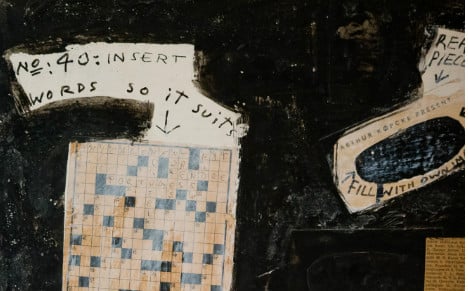

Coming across a crossword in one of the exhibitions, K. saw that she knew the answer to one of the questions. The clue asked for the English for the German word Mauer (wall), so she filled in the answer in the appropriate space.

But this wasn’t just any old crossword.

The 1965 artwork, titled “Reading-work-piece” by Arthur Köpcke, is an excerpt from an unfinished crossword, now worth an estimated €80,000.

Little did the pensioner know what ramifications her action would have.

Filling in only a few boxes on the crossword was enough to catapult her into headlines across the world and land her with a criminal charge.

Since she soared into the spotlight, the retired doctor has been inundated with requests to give interviews and has received invitations to be on talk shows.

But K. isn’t exactly clamouring to hold onto her new-found stardom and has asked the media not to reveal her full name or to publish any pictures of her.

In fact, she doesn’t understand what all the fuss is about.

“Next to the crossword, it clearly stated: ‘Insert words’”, she protests.

So that is exactly what she did.

“It’s a piece of Fluxus art, otherwise I wouldn’t have done it,” K. explains, maintaining that she only did what the artist would have wanted.

Köpcke belonged to the Fluxus art movement, fashionable in the 1960s and 1970s, which often invited the observer to participate in the artistic process.

In the German National Museum, only a stone’s throw away from the Neues Museum, she would have never dreamed of scribbling on works of art. “But in the Neues Museum, it’s different. There are modern artists there,” the old woman adds.

But despite her persuasive argument, the museum will not budge on their strict no-scribbling-on-art policy.

“In our house rules, it clearly states that people are not allowed to deface pieces of art”, says museum spokesperson Eva Martin.

Aside from pursuing her interest in modern art, the old lady has also been contributing to the Writing Workshop Circle of the Evangelical City Mission for several years now.

So if there’s one thing to come out of her escapades in the Neues Museum, it’s that the lady won’t be short of writing inspiration now.

Forget poems about her childhood, the story of how an art defacer feels when waiting to be interrogated at police headquarters will make for a much more interesting read.

K., who lives in Nuremberg but originally comes from Cologne, is convinced that her “Rhine calmness” helped her get through the whole kerfuffle.

“Et es wie et es” (“It is what it is”), she asserts in her Cologne dialect.

It seems that nothing fazes this happy pensioner. “If you don’t feel 100% sometimes, there’s no need to grumble,” she goes on to say.

The old lady maintains her endlessly positive mindset by doing gymnastics regularly, meeting friends to play Canasta once a week, and reading the paper every day.

Until she was 80, she even did tap dancing in a Nuremberg dance school.

“You need to think positively and learn about everything – that keeps you fit,” she asserts.

Meanwhile, back at the Neues Museum, troubled waters have been stilled. The artwork has been restored at a cost of somewhere in the “low three-figure area”, according to the museum’s website, and has been put back into the exhibition.

Museum director Eva Martin has also made her peace with Hannelore K after a clear-the-air meeting.

“Fluxus does indeed call on the public to take part in the artwork, but at some point the action ends,” Martin said.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments