Bernhard Roetzel might not have topped a list of German style icons if you had been compiling one in the early 1990s.

But with the release of his book “Der Gentleman” in 1999, he was on his way to becoming a fixture of the fashion scene.

Leafing through the latest edition of the book – also available in English – you'll find tips on everything from finding a good barber and picking out a cologne, through suits, shirts, ties, and shoes to knitwear – and even jeans.

“Today the classic style is even more sought after than in 1999, and perhaps more sought after than ever,” Roetzel writes in the foreword to the 2016 edition.

The author shows off his knowledge of his subject by not just making recommendations, but going deep into the origins and history of every item.

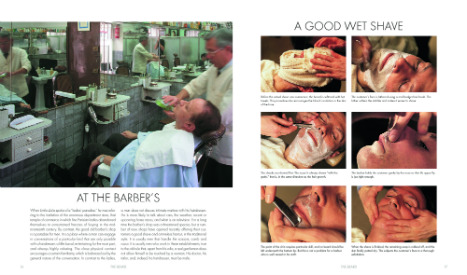

“The good old barber shop is a paradise for men,” writes Roetzel. Photo: h.f. ullmann publishing

“The good old barber shop is a paradise for men,” writes Roetzel. Photo: h.f. ullmann publishing

Attentive readers will learn how to distinguish the different notes of a perfume, how to store cigars, or which Hollywood star was famous for wearing grey flannel trousers on set.

It might not be the guide to up-to-the-minute fashions that will get you past picky bouncers at Berlin nightclubs, but it's one that he claims will make you at home in a more refined milieu almost anywhere in the world.

“As a German, if I want to dress in a good, classic way, so that whether I'm in Milan, New York, London, Paris, or Hamburg I'll look equally as good, I have to choose a style that is English or Italian,” Roetzel told The Local.

Childhood fascination

He himself puts the success of his book and the fashion tips tucked away inside down to a certain type of German's deep love of the United Kingdom.

“In Germany it's a form of exoticism to love this style, almost to dress up as an Englishman,” Roetzel said.

Sipping coffee at a table outside a Berlin cafe, Roetzel could almost have been the picture of an English country gent up for a day in the capital with his waxed jacket, woolly cardigan and loosely knotted scarf.

And behind his neat round glasses and German exactness of speech is an abiding love of Englishness that goes back to his childhood and student days.

London's Savile Row is “one of the last outposts where designing a garment is the province of the craftsman who makes it,” Roetzel writes. Photo: h.f. ullmann publsihing

London's Savile Row is “one of the last outposts where designing a garment is the province of the craftsman who makes it,” Roetzel writes. Photo: h.f. ullmann publsihing

“There were particular English films that I liked when I was a child in school in the 70s,” he explains, name-checking the classic TV series All Creatures Great And Small about a vet in rural Yorkshire.

“Somehow the clothes had a particular aura, a particular history that I found fascinating. That got me interested, it marked me.”

Later, Roetzel spent time in London as a student, snapping up beautiful old hand-made clothes in the British capital's second-hand shops and coming to understand the unbalanced relationship between the two countries.

Cool Britannia

“The Germans always admire and love the British – but for the British, the Germans are just a curiosity,” he explained.

Germans are more likely to be the butt of jokes about the Second World War – a time Brits have found very hard to move past – than the object of admiration.

Roetzel told the story of a visit to a Berlin tailor's shop just before the interview, where as the owner unwrapped a package of material from England he found a joke note with a drawing of a WW2-era Messerschmidt Me 109 fighter plane.

The German-British relationship is“like if a man who isn't particularly attractive has a super attractive wife,” he joked.

“He will always be on his knees before her, while she'll just think he's fine, but…”

All that admiration means that there's definitely a market for classic English menswear – and its offshoots from Italy and elsewhere – this side of the Rhine.

Nowadays Roetzel spends his time travelling around Germany and abroad, writing and giving lectures and readings from his books to his fans – and he's even recently set up a Facebook page.

Even outside his official events, he said, “I see someone walking around in a covert coat [a style favoured by British figures like Prince Charles and UK Independence Party leader Nigel Farage] and I think 'oh, maybe he read my book.”

A style icon to Germans? UKIP leader Nigel Farage wearing a covert coat on a visit to 10 Downing Street. Photo: DPA

A style icon to Germans? UKIP leader Nigel Farage wearing a covert coat on a visit to 10 Downing Street. Photo: DPA

“There's a great fascination for this theme, although it's really a dream world – that's what clothes are for, we choose them for completely subjective, emotional criteria. They express something.”

'The fantasy of an Englishman'

So just what is it that so many of Roetzel's fans in Germany and abroad are trying to express by chasing Savile Row suits or handmade shirts from Milan?

“Well-dressed men dress as their fantasy of an Englishman. This type of clothing is usually chosen to express a certain desired or actual status. Most people think clothing expresses taste, but actually it expresses status,” he explained.

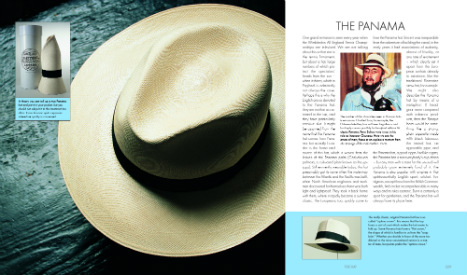

“In theory you can roll up a true Panama hat and put it in your pocket. But should should not subject it to this treatment too often.” Photo: h.f. ullmann publishing

“In theory you can roll up a true Panama hat and put it in your pocket. But should should not subject it to this treatment too often.” Photo: h.f. ullmann publishing

The majority of Germans “have to have something new,” he went on. “Germans aren't good at what's called classic. They're good at modern products, modern architecture, cars, and that extends to fashion too.”

“This classic, old money look of the upper class – that's a way of signalling something in particular.”

And for passionate German fans of the shrinking world of the pre-war English upper class, that cachet is even worth the odd bit of ribbing from a Brit unable to move past the Second World War.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments