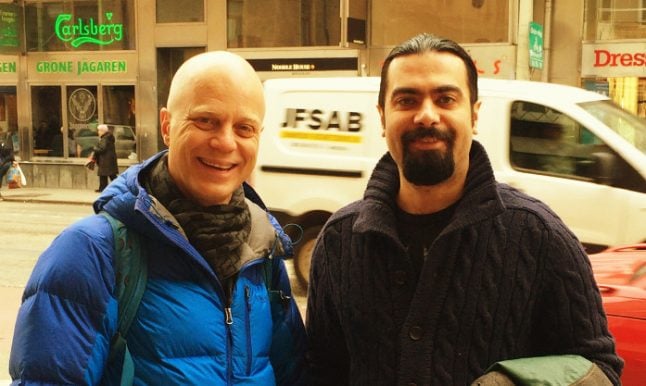

Drinking beer, an obsession with photography, and listening to music are the three commonalities that brought Ali, 32, and Bo, 47, together.

Despite being born in different countries and different decades, they discovered their shared interests thanks to Kompis Sverige (‘Buddy Sweden’), an organization that connects newcomers with established Swedes who share mutual interests.

Ali fled Iran after producing a documentary film and participating in demonstration in connection with the country’s 2008-2009 presidential elections. Soon thereafter, the Iranian security services raided his flat. Luckily he wasn’t home at the time.

“They took my laptop, my phone and everything [related to my activities]. My wife called and told me, ‘Don’t come back, they are here.’”

Ali admits that when he first arrived in Sweden in 2013, he was underwhelmed by the Swedish capital.

“I had a view that Stockholm would have the same architectural grandeur of Paris, but when I arrived here it was really a huge shock,” he recalls.

He learned about Kompis Sverige while enroled in SFI language classes, but at first he wasn’t interested. But after his wife found a “perfect match” through the organization, Ali decided to give it a try.

“I like music and mostly, I go to concerts alone; so I thought, ‘I need to have a friend who likes music and might like to accompany me.’,” he explains.

Meanwhile Bo happened upon a flyer for Kompis Sverige at the Fotografiska museum in Stockholm last year.

“I called them and got to know about Ali. They told me he speaks Swedish – which didn’t matter to me – and that he likes music and photography,” says Bo.

Sitting across from one another on a recent afternoon in Stockholm, several months since they first met, they both wonder if they would be friends today had their paths crossed on a train, in a bar, or at a restaurant.

Indeed, both agree it’s harder for people in Sweden to establish friendships if a service or organization doesn’t take the lead in orchestrating meetings between strangers.

“Here in Stockholm, if you walk to a bar and said hi to people, often they may react like ‘Oh! Scary… a strange guy says hi.’ While in other countries it would be scary to NOT to say hi,” Bo explains.

“And here if you talk to somebody for a while [on a bus or train] they may reply but they wouldn’t try to continue [carrying on the discussion].”

Ali, on the other hand, believes Swedes are restrained and that relationships in Sweden are vastly different to what he used to know back in Iran – a situation that can leave any newcomer wondering how to react, how to get along with people or simply say hi.

“What feels odd to me is that, Swedes are really, really polite, and they treat everyone equally,” Ali reflects.

“But sometimes you can’t know how to interact; sometimes people greet you, and of course you reply. Other times you say, ‘HI!’ and they don’t answer. I got really confused. Should I talk to people or should I not!”

'I've changed a lot'

Ali tells of a recent attempt to say hi to his next-door neighbor, for example.

“She looked at me really strangely and didn’t answer.”

However Bo believes Swedes in Stockholm aren’t as unsocial as they might seem – it’s more about the busy life of cities compared to the countryside.

“If you go up north – people greet each other, and a bystander might even be invited to have a meal with his or her neighbor,” Bo explains.

Back in Iran, being a civil activist engaging with people, participating in rallies and creating documentaries – Ali’s life was full of activity, something that’s changed dramatically since he came to Sweden.

“I’ve changed a lot – it was my rule – always to do something instead of staying at home; before I couldn’t stay at home. But now it’s really difficult for me to get out – I don’t call any one, I haven’t called my parents for six or seven months,” he explains.

“I used to be very talkative, when I first came here I had so much energy and wanted to talk to everyone; but as time has passed on I don`t feel like I want to talk to people anymore – I am not sure if it’s me or the society? I am not sure anymore!”

As he listens to Ali, Bo starts to smile. He reckons Ali should take pride in his perceived transformation and what it likely signifies.

“You see, now you should be super happy,” Bo says as he bursts out in laughter and Ali moves to insert a new portion of snus under his lip.

“You are finally integrated!”

As the laughter subsides, Ali and Bo reflect on how easy it is to fall into generalizations and stereotypes when facing something unfamiliar – and agree it’s important for both Swedes and newcomers not to fall into the trap of making sweeping assumptions based on one person’s actions.

And as Swedish policymakers and citizens argue about the costs and challenges of integration on a national scale, Bo reckons there is a very cheap and efficient way to help newcomers and Swedes understand one another better on an individual basis.

“Is it really that hard to just say hi? After all, that doesn’t cost anything,” Bo wonders.

Ali and Bo head out for a beer before taking in a concert in Stockholm

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.