French writers have never felt more badly paid, undervalued or under pressure, with a new survey showing more than half of established authors earn less than the minimum wage.

Many are so depressed by the state of the book industry that they are considering giving up altogether, according to a new report.

“Authors have a high social status but almost empty bank accounts,” said Marie Sellier, president of the SDGL, one of the five writers' and publishing groups behind the vast study.

Like their counterparts in the US and the UK, French writers have seen their incomes plummet since the 1990s, the report found.

More than a third of even the highest-earning authors had to have another job to make ends meet, mostly as teachers, it said.

Established writers with years of relative success behind them struggled to make a living, with their median annual earnings of €17,600 ($19,800), less than three-quarters of national average.

The most staggering statistic of all in the report, which was backed by the ministry of culture, is that six out of 10 published writers make less than €1,500 a year ($1,700).

Grim reading

Despite French publishing growing for the first time for five years, authors remained deeply downbeat about their prospects.

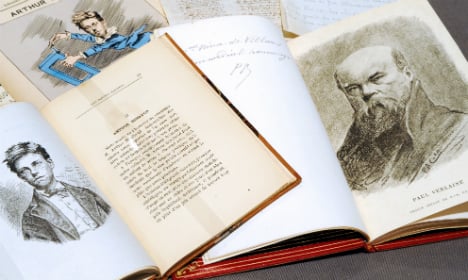

The survey of more than 100,000 fiction and non-fiction writers as well as poets, illustrators and translators found they were they “generally worried, disenchanted and discouraged.

“Many were asking themselves whether they should diversify into other work or stop altogether,” it concluded.

Although exact comparisons are difficult to make, French writers appear to be still doing better than their British or American equivalents.

Established British authors tend not to make even half the industrial wage, with latest data showing them averaging 11,000 pounds (14,000 euros) a year.

Nor has the boom in self-publishing and e-books made much difference to writers' often miserable earnings, according to the Authors' Licensing & Collecting Society.

An online US survey last year by Digital Book World made even grimmer reading, finding a third of published authors earned less than $500 a year from their writing.

Philip Pullman, president of the British Society of Authors, placed much of the blame at the feet of Internet giant Amazon and publishers when the last round of British statistics were published last year.

“While Amazon makes earnings of indescribable magnitude by selling our books for a fraction of their value, and then pays as little tax as it possibly can, the authors whose work subsidises this gargantuan barbarity are facing threats from several directions,” said the author of the acclaimed His Dark Materials trilogy.

“In the past ten years, while publishers' earnings have remained steady, the incomes of those on whom they entirely depend have diminished, on average, by 29 percent.”

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.