Andreina climbs a ladder so that she can reach the high shelf where a dozen or so dusty bottles of wine stand at her restaurant in northern Rome.

She takes a couple down and proudly shows them off, not because they’re part of a vintage collection, but because they’re emblazoned with photos of someone she considers to be a hero, Benito Mussolini.

Alongside the bottles is a photo of the fascist dictator’s bed at Villa Torlonia, the Rome residence he rented for one lira a year, and another grainy image of him standing bare-chested next to a small crowd.

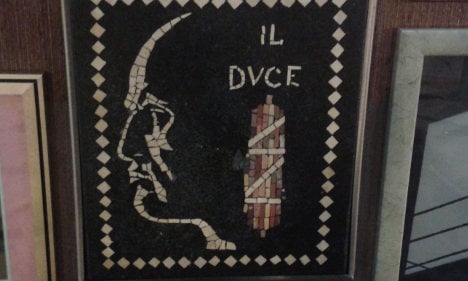

More visible to diners in the small restaurant in Rome are the collection of Mussolini calendars and other photos of ‘Il Duce’, the title he gave himself after dismantling democracy and making himself dictator, that adorn the walls.

Mussolini is one of the most reviled men in Italian history, but Andreina, who is in her 70s, doesn’t care that the shrine might deter or offend customers.

“It’s part of history, our culture, and I’m not changing it,” she tells The Local.

It’s almost 70 years since he was captured and shot dead by partisans, before his body was strung up with piano wire in a Milan square, but the spirit of Mussolini is still alive and well among some factions in Italy.

Mussolini led the country for over 20 years. During that time he introduced anti-Jewish laws, formed an alliance with Hitler, and sent thousands of Italian Jews to death camps.

He also gaggled the free press, had political opponents arrested and, in a bid to make amends with the Catholic Church after declaring himself an atheist as a socialist youth, tried to suppress homosexuality by sending gay people to internal exile on San Domino, an island in the Adriatic.

For the vast majority of people – including most Italians – this makes Mussolini one of the chief villains of the Second World War. Yet, extraordinarily, and despite his defeat at the hands of the Allies, some Italians like Andreina openly parade their admiration for 'Il Duce'.

“He made mistakes,” she admits. “But if it wasn’t for him, I wouldn’t have gone to school. Things got done when he was leader. He built houses, stadiums and roads, he introduced pensions…before, you worked and got nothing.”

In a sense, it's the old cliché of the trains running on time, but it goes beyond that too.

Mussolini’s leadership “restored order”, Andreina insists, and “made the country stronger”.

Like many, she contrasts modern Italy's chronic economic and political woes with the supposed order of the Mussolini era: “Today Italy is destructive, we’re in deep trouble.”

Roberto Chiarini, a professor of contemporary history at the University of Milan, says the Mussolini admirers of today see him as a hero, and want to believe he “wasn’t that bad”, at least not as bad as Hitler.

People flock in their thousands each year to the Emilia-Romagna town of Predappio, where Mussolini was born and is buried.

Predappio Tricolore, a souvenir shop, does a brisk trade selling memorabilia, owner Pierluigi Pompignoli tells The Local, with “young people, not all neo-fascists, travelling from afar”.

“They’re people who’ve informed themselves,” he tells The Local by phone.

“They’re also fed up with an Italy they see as no good and where there is no more respect. A lot of young people travel here especially to find out more.”

The store has also managed to capture an online market through its website, which has everything from Mussolini mugs and key-rings to cushions and statuettes on offer.

Christopher Duggan, a history professor at the University of Reading in the UK, has written extensively about Mussolini and Italy’s fascist era. He also travels to Predappio several times a year for his research.

“It’s not all just 25-year-olds with shaved heads,” he tells The Local. “It’s average-looking families who have this vision of a man who helped make Italy great.”

Duggan says this positive vision is partly because Italy has still not really come to terms with what happened in the 1930s under fascism.

“Unlike other countries, Italy has never really squared-up to it. Any discussion on fascisms’s darker side has been mute or even actively repressed. It’s still very difficult to speak about it publicly, and it’s hard for serious academics to raise issues that might suggest that Fascist Italy was not morally much different from its Nazi ally.”

The rise in the number of Mussolini admirers has gathered pace since the mid-1990s, when Silvio Berlusconi first became prime minister.

His glowing rhetoric about fascism since then has helped to rehabilitate Mussolini, explains Duggan.

At a ceremony in Milan to commemorate the holocaust in January 2013, he defended Mussolini for allying with Hitler, saying the dictator probably reasoned it was “better to be on the winning side”.

He also praised him for “having done good” and said Italy “did not have the same responsibilities as Germany”. Last year, his Forza Italia party fought an ultimately unsuccessful campaign against plans by the city of Turin to revoke Mussolini's status as an honorary citizen of the city. All of this coincided with a campaign to denigrate anti-fascism.

“This has made people think it was positive,” Duggan says.

The hugely controversial role of the Catholic Church, with which Mussolini fostered good relations to gain strength and moral legitimacy for his regime, is also crucial in influencing how fascism is remembered.

“You can’t get away from the massive support for fascism from the Catholic Church,” Duggan says.

Seventy years after Mussolini death, and with the church failing to lead by example and completely address its role in Fascist Italy, many Italians remain unwilling to recant their own support for Il Duce.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments