Fastelavn can roughly be described as a Danish version of the pre-Lent Carnival tradition associated with Roman Catholic countries, in which children wear costumes and go out asking for candy or money.

We know what you’re thinking: that sounds more like a Danish Halloween. Careful now. Fastelavn versus Halloween is a topic that can raise heated discussions. The former is rooted in medieval tradition seasoned with Danish touches, while the latter concept has only began to grow in popularity over the past generation.

“Kids love it. They get to dress up in costumes twice a year, and it’s a big thing at school and day care,” says mother of three Tove Spissøy Gerhardsen. “But costumes are expensive so we don’t make as much out of Fastelavn as we do Halloween. And of course, a youngster cannot go dressed as, say Superman, for both days. In general – and I believe a lot of other parents share my opinion – Halloween costumes may have a higher priority, but everybody still enjoys Fastelavn.”

While Halloween may cause many people to shake their heads at what they consider to be nothing but a money-maker for businesses catering to a non-Danish holiday, Fastelavn is a more integral part of Danish culture. Few people would attach any religious significance to either, though both are directly connected to Christianity, but with obscure links to good old paganism.

OK, so Fastelavn is not Halloween. What is it, then? Glad you asked! Here are a few things you need to know about Fastelavn.

‘Something to do with Lent?’

Flæskesteg or roast pork is also eaten by Danes at Christmas. File photo: Ida Guldbæk Arentsen/Ritzau Scanpix

Fastelavn will be celebrated all across Denmark this Sunday, but few people seem to know why. Although the name of the day ought to give some kind of hint, not one of the 16 random Danes polled by The Local on the streets of Copenhagen could explain the reason for celebrating Fastelavn. “It either begins or ends the fast [Lent, ed.],” was the closest guess.

Fastelavn was basically the feast before the fast, the 40 days of Lent beginning on Ash Wednesday and ending on Easter Sunday. It was originally a three-day binge: Flæskesøndag and Flæskemandag – Sunday and Monday when flæsk (pork, but akin to flesh) was eaten – meat, as in the Latin carne, hence carnival; and, White Tuesday, when revellers consumed dairy foods and the special buns described in the next point. Lent disappeared after the Reformation, but celebrations continued. Scrap the fast, but keep the feast.

Fastelavnsboller can take a range of forms. File photo: Thomas Lekfeldt/Ritzau Scanpix

Fastelavnsboller (buns) are these days mostly eaten on the Sunday now known as Fastelavn, but traditionally the sweets were for White Tuesday, the day before Ash Wednesday.

What are Fastelavnsboller? Well, one website had more than 70 recipes for “traditional” Fastelavnsboller. Our favourites are cream filled and topped with chocolate. Many families will involve their children in baking and decorating the buns, but of course eating them is the most fun part.

Dying traditions

Photo by Samuel Jerónimo on Unsplash

In some places, various traditional celebrations live on such as ’tilting at the rings’, that is: galloping at full speed on horseback and trying to place lance through a ring. Leave this one to the pros.

Other traditions have mercifully died out, like hanging a goose upside down, greasing its neck and holding a competition to see who could yank the bird’s head off. Or, trying to smash an inverted clay pot with a bat while blindfolded. Under the pot was a live rooster buried up to its head. It’s probably little consolation, but the birds were eaten afterwards.

The one tradition that has thrived through the years is “knocking the cat out of the barrel,” a game played in schools, day care institutions and around homes. Like a piñata, a barrel is hung and youngsters try to smash it with a bat. When they do, a pile of sweets fall out. In the old days, a live cat was used, preferably black as a symbol of evil.

Knocking the cat out of the barrel on Fastelavn in 2014. File photo: Søren Bidstrup/Ritzau Scanpix

The winners of the modern day cat-in-a-barrel game are crowned as the Cat Queen (Kattedronning – the one who knocks the bottom out of the barrel) and the Cat King (Kattekonge – the one who knocks off the last remaining board), although the goodies are divided evenly among the kids.

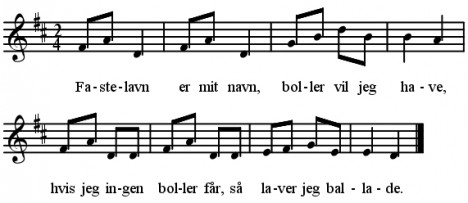

Kids may knock on your door. They will be rattling coins in what look like non-piggy-formed banks. The ditty they sing warns that if they don’t get those sweet buns they will make trouble (see below for Danish and notes).

But don’t worry, you don’t need to have baked goods on hand – despite the song’s lyrics, the kids really want you to put a few coins in their banks. A few generations of parents have frowned upon the practice, as have miserly neighbours. Modern parents, perhaps influenced by Halloween, often prefer their youngsters to ask for sweets.

Some grown-ups may wear a costume when accompanying their kids to a Fastelavn function, but they do not hold parties for Fastelavn as they might on Halloween.

Photo: WikiCommons

Article originally published on February 14th, 2015

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.