Scientists from the Karl May Museum in Radebeul, near Dresden will work "in close cooperation" with members of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, who say the scalp came from a mid-19th century member of the Ojibwa tribe.

"In respect for the collective feelings of the Chippewa Indians, we are going to conduct our joint research work on the scalp with the highest possible scientific accuracy," said museum director Claudia Kaulfuss.

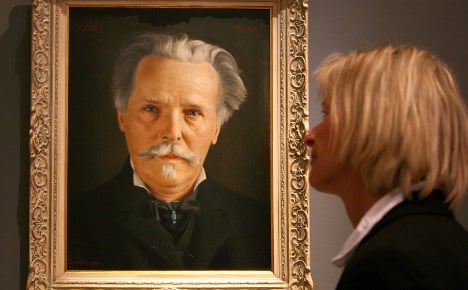

The private museum opened in 1928 and is dedicated to the works of popular German adventure writer Karl May and to the cultural heritage of American Indians.

The museum acquired most of its 17-scalp collection from a friend of May's. Ernst Tobis, known more commonly as Patty Frank (his stage name). Frank was a traveling Austrian circus artist who collected items from American Indian culture and co-founded the museum with May's widow, Clara.

Myth or reality?

Cecil Pavlat, the repatriation specialist of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians in Michigan, bases his claim on a caption for a photo of the scalp in a story written by Frank which was published in a book in 1929.

It has not yet been verified who wrote the photo caption, a spokeswoman for the museum Anne Barnitzke told AFP.

"Therefore it's not really clear if the story he tells is real," she said

In the story, Frank writes about how he acquired his first scalp, originally belonging to a chief of the Ojibwa tribe, in exchange for 100 dollars and three bottles of liquor.

But Pavlat stands firm.

"These are human remains which should be buried respectfully and should never have been taken from the tribe in the first place," he told The Guardian in March.

Museum director Kaulfuss stresses that they do not seek to misrepresent a piece of Native American history and that the exact tribes to which the scalps belonged to is not yet clear.

"We're a museum in Germany, subject to German law, and we'd like to explain why we want to show a piece of history" she told the Deutsche Welle.

"They can't just expect us to hand something over without talking to anyone about it first, because then more people might come and soon our museum would be empty" she added.

Claims of repatriation in Germany are not as uncommon as one might think.

In 2011 Germany handed back 20 skulls that were from Namibian tribal leaders, government officials and descendants of Herero and Nama victims massacred by German imperial troops.

And in 2013 a German hospital said it had handed over remains from 33 Aborigines to Australian representatives to be returned for burial.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments