Several leading unions in the education sector have threatened to strike on Wednesday and the influential Academie Francaise, set up in 1635 and the official authority on the language, has led a chorus of disapproval.

The country has for decades zealously propagated the use of French both at home and abroad through cultural institutions and the French-speaking Francophonie bloc of nations.

But the use of English has made rapid inroads at home with the vast majority of French youths learning the language and using it on a near-daily basis. Many now respond to telephone calls with an energetic "Yes?" in place of the traditional "allo" or "oui".

English is seen more and more in graffiti in Paris and "franglais" is gaining ground. People pepper their sentences with expressions such as "why not?", instead of the French equivalent "pourquoi pas?"

Higher Education Minister Genevieve Fioraso has said the measure is aimed at increasing the number of foreign students at French universities from the current level of 12 percent of the total to 15 percent by 2020.

But even fellow members of her ruling Socialist party have opposed the plan.

Pouria Amirshahi, a lawmaker representing French expatriates living in north and west Africa, was cutting in his criticism.

"The signal given out to those everywhere who learn French is not reassuring," he told AFP.

Although the proposed plan foresees the use of English or other foreign languages for only a part of the course, it is still "unacceptable," critics said.

"It is the cultural heritage which is at stake," said Claudine Kahane, a senior official of Snesup-FSU, one of the main unions in the education sector.

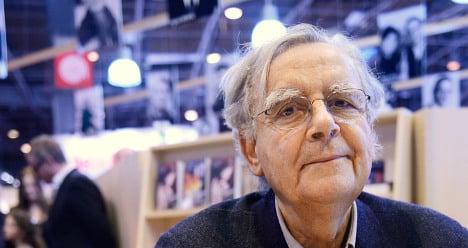

Journalist Bernard Pivot, a leading figure in French cultural circles, said it could sound the death knell for what locals quaintly call "the language of Moliere."

"If we allow English to be introduced into our universities and for teaching science and the modern world, French will be vandalized and become poorer," he said.

"It will turn into a commonplace language, or worse, a dead language."

But the case for English is gaining ground in an era of globalization. The French economy is currently in recession with double-digit unemployment and many people fear they might eventually have to work abroad.

Fioraso on Wednesday said the controversy was unjustified.

"Today there are 790 training courses mainly in English … and nobody is shouting," she said.

Khaled Bouabdallah, vice-president of the conference of the heads of universities, said: "We have been in favour of this for many years.

"Foreign students who normally shun our universities will come", and "for our own students the mastery of English is an important aspect," he said.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments