“If we can’t turn the tide around I really don’t see much of a future,” the municipality’s integration coordinator Gunilla Nyberg tells The Local.

The population of the town of Jokkmokk, located just north of the Arctic Circle, has steadily shrunk since its peak of around 4,000 in 1990 to less than 2,800 today.

The municipality at large has seen a similar decrease – half of its residents have left since the 1960s.

Nyberg is part of a team welcoming those who want to move to the village, which has played host to the eponymous Jokkmokk market for more than 400 years, in hopes of replenishing the town’s dwindling population.

A furnished flat at discounted rent stands at the ready for people who just want to visit and scope the place out, or as a temporary solution while they find work and a place to stay.

Nyberg’s team has even struck a deal with the local municipal tenancy organization so newcomers can get a roof over their head quickly.

“If they’ve lined up a job, they’re in the VIP lane for flats,” she says, also pointing to low property prices for anyone wants to buy.

“You could buy an entire block here for the same price as a flat in Stockholm.”

On hand to give advice are Englishman David Carpenter and his wife Kerstin, themselves relative newcomers.

Quarter-Swedish Kerstin took over her grandparents’ house in Jokkmokk eight years ago.

“We were here most summers and it just got harder and harder to go back,” David says about the decision to move here permanently.

“It’s so vast, there is such a huge sense of space up here. England is a great country but it’s become so crowded,” he tells The Local.

He and Kerstin have been roped into the Jokkmokk Future Project to offer practical advice on anything from getting a personal identity number (personnummer) to making sure children are registered for school.

“It’s quite confusing, people can get bounced around a bit,” he explains.

He himself had to wait about six months before getting the identity number, which opens the door to many administrative services in Sweden.

Finding jobs could be the least of the newcomers’ problems, says Carpenter, citing the local shortage of nurses, teachers, drivers in the nearby Gällivare mine, and plumbers.

The oddest question he was ever asked was where Father Christmas lives.

“I said he’s here but we don’t see him very often, but we see his foot prints in the snow,” Carpenter recalls.

The project has web sites in English, Dutch and German but Carpenter says there are Venezuelans and Bulgarians among the 30-odd families who have moved to Jokkmokk recently.

Multiculturalism comes naturally to Jokkmokk residents, he says, because they are a mix of ethnic Swedes and the Sami.

And being a small town works in favour of integration, adds integration coordinator Nyberg.

“You’re seen as a person rather than just another face in the crowd,” she says.

And long-term residents are positive to the initiative, she says.

“We need tax payers and resources to uphold the level of social security that we despite everything still offer,” she said.

Nyberg’s own two children have stayed in the north but many youngsters do not.

Some buck the trend, however.

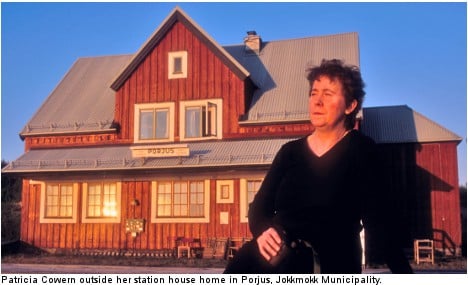

The son of Patricia Cowern, an English transplant to Jokkmokk, decided to follow his mother’s lead and set up a life in Sweden’s expansive north.

“I came in 1996 on holiday with him, then I moved here and bought the Porjus station house,” Cowern tells The Local.

Her son and his family joined her in 2000.

“My grandchildren are more Swedish than they are English.”

Cowern does notice that many young people do head off once they graduate from high school.

“There is that gap of people between 18-30. The young girls leave to go to university and they don’t come back,” she says.

“They don’t come back until they get married and have children. They come back, I think, because bringing up a child in a city is quite a different experience.”

Like the Carpenters, she praises the vastness of the landscape, and its beauty.

The Sarek National Park, classified a world heritage site by Unesco, lies within the municipality’s borders.

Last winter, Cowern took part in the Jokkmokk market, and asked municipality officials how many foreign-born residents the community now had.

“I was astounded that there are 37 different nationalities here,” Corwen tells The Local.

“Well, I mean, with the Swedes there are 38.”

Ann Törnkvist

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments