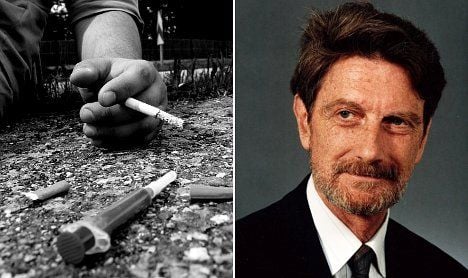

“The Swiss population has generally always had a high addiction liability in comparison to other European countries, in alcoholism, cigarette smoking, and in illegal drugs as well,” says 83-year-old Professor Ambros Uchtenhagen, president of the Addiction Research Institute at Zurich University and consultant to, among others, the World Health Organization.

The heroin problem reached its pinnacle in Switzerland in the 1980s, when cities such as Zurich and Bern became famous for their open drug scenes. These hubs attracted large numbers of drug users from all over the country and beyond.

The scene brought with it drug dealers and crime, as addicts burgled and stole to feed their habits. In an effort to keep the heroin users where they could see them, the police eventually decided to let them take over the city parks. This way, at least the police could keep an eye on them and provide emergency assistance for the frequent cases of overdose.

Professor Uchtenhagen, who had set up the in- and out-patient and rehab clinics as part of the University of Zurich’s social psychiatry arm, also set up and participated in the mobile emergency teams that would regularly revive overdose patients.

When the scene was at its most extreme, thousands of injectors occupied Switzerland’s green public spaces, he tells The Local. Shared needles caused HIV to spread quickly among users, and it was feared that the disease would spread by sexual means to the non-injecting population.

The parks were unsightly blemishes on an otherwise impeccable landscape and acted as constant reminders to the public of the existence of the problem. Something had to be done.

At first, the authorities tried to control the heroin addicts by punishing them with severe sentences and a zero tolerance attitude. But the strength of their heroin addiction meant that, for most, the threat of legal action was hardly a deterrent.

“We soon realised law enforcement doesn’t change a thing,” Professor Uchtenhagen remembers.

When legal means alone failed to tackle the problem, a new concept was introduced with the aim of reducing the negative consequences of heroin addiction, both for the individual and for society as a whole. Harm reduction, as it became known, soon formed the fourth pillar of Swiss drug policy, alongside the concepts of treatment, prevention and law enforcement.

The introduction of needle exchange programmes, for example, helped prevent the spread of diseases.

“At a relatively early stage our public attitude changed from viewing heroin addicts as criminals, to an image of patients in need of appropriate treatment.”

This pragmatic attitude enabled professionals from a range of disciplines including law enforcement, health, social services and politics to combine efforts to find a range of solutions to the host of issues surrounding heroin abuse.

Professor Uchtenhagen was a member of the Federal Drug Commission at the time, and was responsible for the development and implementation of the research into the use of heroin as a form of treatment.

As a result of these concerted efforts, the Swiss were the first to set up the controversial heroin-assisted programmes in the 1990s. These programmes were targeted at the small proportion of users who did not respond to methadone treatment, enabling professionals to tackle some of the more difficult, hardcore cases.

It is perhaps surprising that such a small, culturally traditional country such as Switzerland should spearhead such an unconventional action plan.

“Switzerland is a very conservative country. But we are also pragmatic,” says Uchtenhagen.

“It is in the Swiss character to want to find out ourselves what’s good for our people, and not to follow the example of others blindly.”

Those working on the projects knew it was crucial to keep the public informed in order to gain their trust.

“Public availability of trustworthy information, on process and outcome data, was paramount,” Uchtenhagen wrote recently in a case study on drug policy.

With his first-hand experience, Professor Uchtenhagen was elected as Chair of the Cantonal Drug Commission, which liaised between the authorities and those on the frontline, and published reports including situational analyses and recommendations for action.

At the time, opinions diverged greatly and not everyone embraced the radical proposals, particularly outside the German-speaking part of Switzerland, which was more affected than other areas.

But the programmes yielded impressive results, and won over many critics, both at home and abroad.

“Other countries started much later with elements such as harm reduction, experimentation, and research on heroin-assisted treatment, so this all contributes to our more visible success,” Professor Uchtenhagen says.

Results from the programmes informed changes in drug policy in the late 80s and 90s, which in turn dramatically reduced the heroin problem.

Police cleared the so-called “Needle Park” in Zurich in February 1992, and addicts were dispersed all over, which was a catastrophe. The scene reformed in an unused railway station nearby and got even worse.

Health professionals responded with a surge in activity: treatment capacity was increased, shelters and day programmes were provided, and low threshold contact and counselling centres were set up throughout the canton. The result was an infrastructure of medical and social care, which helped prevent the same catastrophic consequences when the scene at the railway station was finally closed down in 1994.

In the same year, new clinics for heroin-assisted treatment for the most chronic and marginalised addicts were set up.

Since 1991, deaths as a result of overdose have reduced by approximately 50 percent, and the instance of HIV infections has reduced by 65 percent.

In 1998, the Swiss people voted in favour of the four-pillar policy with a two-thirds majority, and in 1999 a majority voted in favour of continuing heroin-assisted treatment.

Although these results herald good news overall, the fact that the problems are no longer as visible as they once were has had an unintended negative effect – funding to keep the programmes going is no longer as forthcoming as it once was.

“There are other priorities now on the political agenda so it’s not so easy to keep going with the things that we have been setting up and to launch new ones to meet the drug problems of today,” Professor Uchtenhagen laments.

Having dedicated most of his life to working with addictions to substances like heroin, the professor refuses to give up.

He now has his eye on new experiments aimed at Switzerland’s most profuse and popular drug: cannabis. Whether the new experiments turn out to be as successful as the heroin projects remains to be seen.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments