The Swedish words “hon” (she) and “han” (he) are loaded with preconceptions about characteristics and we see that language and the words we choose have a huge impact on how we experience the world.

The new gender-neutral Swedish word “hen” will open up for a freer interpretation by not being tied to these preconceptions.

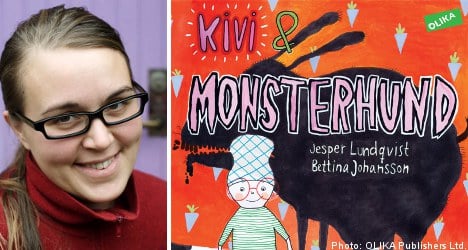

Despite the fact that the book “Kivi & Monsterhund” (‘Kivi & Monster Dog’) hasn’t been published yet, we have already received a number of reactions.

Many are positive and curious.

Others feel that it is upsetting and threatening, as gender is seen as something important. It creates predictability and safety. It is perceived as problematic when someone breaches the expected gender roles and in many cases it leads to some sort of punishment.

In 2011, a young boy in Jönköping was attacked for wearing pink and nail polish, which are perceived as female attributes.

Today, “han” (he) is automatically used when we don’t know the gender of a character and old Swedish rules on writing dictate that “he” should be used when the sex is not known or is deemed irrelevant – which can be seen in many legal texts.

And there are all the children’s books where seemingly gender-neutral characters and animals almost always are male.

“He” becomes the norm and anyone who is supposed to be a “she” has to stand out by expressing her feminine attributes. A child who erroneously calls someone “he” is quickly corrected and learns that it is important to make a distinction between “he” and “she”.

We argue that this should be of secondary importance and that the active separation of the sexes has negative consequences for both individuals and society.

A more relaxed attitude with a less prominent gender indoctrination would lead to a better future. To bring the Swedish word “hen” into common usage is part of that work.

In “Kivi & Monster Dog”, it doesn’t matter if it is a he (han) or a she (hon); a gender-neutral “hen” can combine characteristics and attributes according to individual preferences, and in the long run lead to neither “he” nor “she” being so strictly tied rules on gender.

“Hen” is therefore a solution that makes it possible to meet the world in a more unbiased way and to read a text or have a conversation where the focus is shifted away from gender identity to the personal characteristics of the individual.

A counter-argument could be that the word “hen” would mean that differences between the two gender roles are erased. But exactly what differences are important to keep?

Salary differences, the use of violence, the providing of care or the capacity for kindness?

We think everyone should be allowed to be different, regardless of sex. According to the latest reworking of Sweden’s laws on discrimination, one can now also claim to be discriminated against due to “cross gender identity and expression”, which also shows that the word “hen” is needed for those who are unable to identify with either gender.

By freeing the word “hen” from the expectations tied to traditional gender roles, readers are given a possibility to meet Kivi in a different way.

This is an exciting linguistic possibility! Why forfeit that chance?

We argue that “hen” is needed if an writers like Jesper Lundqvist, the author of “Kivi & Monster Dog”, wants to succeed in letting the character be evaluated from its individual characteristics and give all children the chance to identify with it.

Bringing in a new element that makes us think about how we use language allows for awareness and change which goes beyond any single word.

Using “hen” doesn’t mean we need to get rid of hon (she) and han (he).

Rather, it’s simply a matter of adding hen: to allow for three choices, instead of two.

Karin Milles, lecturer in Swedish, Södertörn University College

Karin Salmson, OLIKA Publishing Ltd

Marie Tomicic, OLIKA Publishing Ltd

This article was originally published in Swedish in the Svenska Dagbladet newspaper. Translation by The Local

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments