According to new research from Lund University, in southern sweden, it is possible to control and even deliberately forget memories.

This new knowledge could be life-changing for patients suffering from depression or post-traumatic stress disorder.

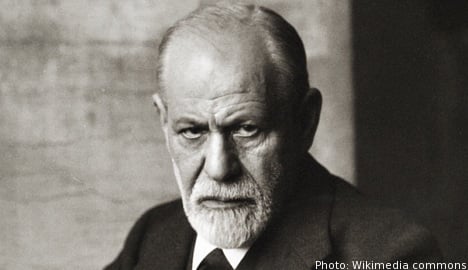

“(Freud) was right in that there is a particular way we can control our memory,” Psychology researcher Gerd Thomas Waldhauser told The Local.

The idea that humans can control their memories erupted in controversy within the field ever since the great Freud argued it in the early 1900s.

Freud’s theory was based on major assumptions while new theories, better theories, emerged related to childhood memory supression and memory development.

“He had no experimental evidence and at that time there was a big debate going on about the reconstruction of repressed memories not always being correct,” Waldhauser said.

“In our laboratory, we can now show that intentional attempts to forget, or suppress particular information or experiences can indeed lead to later forgetting.”

The major breakthrough is finding that the brain uses the same area for inhibition of memory as it does for inhibition in motor skill response.

“It’s quite important to have established this link. It hasn’t been done before, it hasn’t been known,” said Waldhauser, who added that his findings resulted from very controlled experiments with results tough to explain otherwise.

Using word association and the electroencephalogram (EEG), a sophisticated brain imaging technique, Waldhauser proved that the same area of the brain which controls motor impulses and selective attention is activated when a person attempts to forget something.

For example, if a person sees a flower pot falling from the table, they will reflexively catch it; however, if it is a falling cactus, they will choose not to catch it.

“This link means that people can actually train themselves to forget memories that are too overwhelming or intrusive just like they can train themselves how to physically react,” said Waldhauser, who has worked with various theories and experiments related to this find for six years.

The experiment involved hours of word association work, asking participants to learn random material such as “car is to banana”. Once thoroughly learned, they were told to no longer remember certain word pairings while retaining others through repititious testing.

“We found that the words we asked subjects to forget, such as banana, were remembered less or forgotten more than words we did not ask them to supress,” explained Waldhauser to The Local.

Although he said more research is needed regarding the long-term outcome of forgetting traumatic memories, such as the physiological effects, the Lund researcher already suggests a few clinical benefits of such a find.

“It might be a helpful intervention tool in the short term for people dealing with depression or post-traumatic stress. It can help them gain back control of their memories,” Waldhauser said.

People suffering from depression might be helped by learning to forget certain aspects that keep them spinning in a vicious cycle of negative thinking patterns, thus helping them break the circle.

The same idea can be applied to post-traumatic stress syndrome patients who are so overwhelmed with traumatic memories that it interrupts their daily living.

Waldhauser told The Local that thus far his research has been positively received amongst his global peers.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments