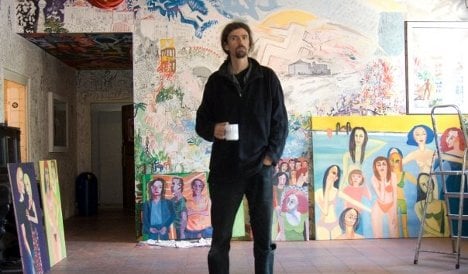

Paul Woods likes chairs. “Some artists do landscapes, some do portraits, I do chairs,” he says, and he has scrawled thousands of little black ones over the walls of his legendary Gallery Wallywoods.

Its current incarnation resides in the Kulturhaus Peter Edel, an old East Berlin cultural centre in the German captial’s Weißensee, named after an Auschwitz survivor turned Communist writer turned Stasi informant.

In the middle of this swarm of insect-sized furniture, Paul, aka Paradox Paul, aka Wally, is building twelve giant chairs – thrones, actually – out of a set of derelict pianos. “Each is also an execution machine,” he adds pointedly.

Wallywoods is more than a studio and a gallery. In the last five years, it has become a teeming venue and working space for Berlin’s avant-garde, a place where live performance, painting, sculpture and extremely loud music constantly gets thrown together by and with Berlin’s most committed punks, drunks and general eccentrics. It’s a place where you are equally likely to see rap, poetry, wall-painting, mock machete fights, or get caught in an impromptu techno party.

Click here for a Wallywoods photo gallery.

Unlike other artistic communes though, there’s no mutual self-satisfaction here – the people who work in Wallywoods seem to derive their creative energy from a relentless quarrelsome restlessness born of frustration. When describing the history of Wallywoods, Paul dismissively alludes to fights and instances of “attempted murder,” then enthusiastically tells the story of a 14-year-old boy who showed up one night, displayed a precocious talent for percussion, spent 45 minutes smashing up a keyboard, and then disappeared.

Paul’s friend, a performance artist known as the Shitty Listener, says Wallywoods represents “the squat scene that isn’t a squat.” The Shitty Listener enjoys listing the luminaries of Berlin’s underground who have graced the Wallywoods stage – Bruno Adams, Nikki Sudden, Alex Tornado – people as little known in the mainstream as they are revered in specialised circles.

Another friend of Paul’s, the Swiss painter Cecile Lutta thrived in the open atmosphere, where strangers could come in, drink beer, and suggest improvements while she was painting. “I worked so well here, you can’t imagine,” Lutta says.

But now Wallywoods is threatened with closure. The district council of Pankow, to which Weißensee belongs, considers Paul’s contract for temporary use of the Kulturhaus terminated, even though he continues to pay the rent, and is waiting for him leave.

But Paul refuses to comply, for several reasons. He want to finish his execution thrones, of course, but he has also developed a deep love for the Kulturhaus Peter Edel itself. Apart from the ground floor rooms occupied by Wallywoods, the facility includes a concert auditorium, a jazz bar, vast gallery space and much attendant technical equipment.

Doomed to be derelict?

Since the council has no immediate plans for the building – the public funds for keeping a cultural centre in Pankow were cut two years ago – Paul believes that his presence is protecting it from dereliction. A private theatre school, Die Möwe, was meant to take over this year, but negotiations have stalled indefinitely.

But the main reason why Paul is staying is a typically Wallywoods-esque combination of indignation and bloody-mindedness in dealing with authority. Last summer he was ready to leave in search of a new space, but a wrangle over when he would leave led him to ask if he could stay. His answer was a bureaucratic brick wall.

“I’ve been saying till I’m blue in the face: ‘Tell us what the costs are on the whole building, or these separate rooms, and we want to pay them!’ But they won’t listen to us,” he says exasperatedly. “They don’t want any of our ideas.”

So Paul decided to fight it out, and his tireless efforts have made him the nemesis of Left party councillor Christine Keil, on whose desk the case has landed.

Both Keil and Matthias Zarbock, Left party culture spokesman for the district of Pankow, claim that the district is looking for private investors with cultural ideas for the building, but they refuse to discuss details or be interviewed. If no investor can be found, the most likely fate for the building will be the open market, where its demolition can no longer be prevented.

Paul has drawn up a series of proposals for the continued use of the space, but Zarbock and Keil are unwilling to discuss them because, they say, he is an “unreasonable partner.” Political deafness has stirred Paul’s determination. “I feel offended that they’ve not listened to our fantastically creative, financially creative ideas – no, they’d rather let it rot, let us rot and eventually make more money.”

One reason why Paul is building execution thrones – apart from to satisfy his chair-mania – is to keep warm. Not only has the water been turned off, the caretaker has taken a hacksaw to the pipes, scuppering the heating for good. Paul’s few portable gas heaters have to be used sparingly, and the big rooms of the Kulturhaus take a lot of warming up. So when he is not fixing guillotines to his sculptures, Paul is often under two duvets, hacking at an old computer, from which he writes letters to politicians and newspapers, or appeals for help on social networking websites.

Until now, and despite universal pessimism amongst his friends, Paul has managed to put off the council one month at a time, using creative excuses to avoid returning the keys. The first was to explain that he needed extra time for storage purposes; then he bought more time by insisting on negotiations for further usage.

Eventually, Paul organised a demonstration to save the Kulturhaus. He and around 40 friends marched ten minutes down the road to Pankow town hall with “Save Culture” banners, an official police escort, and, of course, a giant chair on wheels. Paul claims that since this show of defiance the caretaker has stopped hacking the heating system to pieces.

“Keil’s under a lot of stress now. They didn’t like my demo where we went to the town hall and banged drums outside and I walked up the steps with a bucket on my head, and gave her a public letter,” Paul reminisces gleefully. “Let’s see if I can find another method to hinder their eventual plan – to lock up and destroy the building.”

But Paul knows that his month-to-month luck will run out eventually and he will have to move on. Ever the survivor, he’s already busy working on a new project, called Paradox Berlin, which is set to rise out of the chaotic ashes of Wallywoods.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments