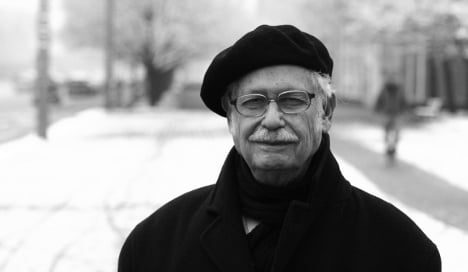

Appropriately for a lifetime leftist, Victor Grossman tells his story while sitting in his favourite easy chair in his apartment on Berlin’s Karl Marx Allee.

Twenty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the 81-year-old recalls how he was one of the few people in the now reunited German capital not celebrating on November 9, 1989.

West Berlin “frightened me,” he says, explaining how he feared the US troops stationed there would arrest him for his hasty decision to desert from the US Army when he was a 24-year-old soldier in 1952.

“For a year or two later after the Wall went down, I still never went across as long as the US Army was there,” Grossman says, his New York accent still strong 57 years after leaving the United States.

Born Stephen Wechsler in New York City, Grossman changed his name upon arriving in the now defunct German Democratic Republic (GDR).

“I said maybe I should protect my family from the consequences of deserting, so therefore I should change my name,” Grossman explains.

“The Soviet officer in charge of me said: ‘Go ahead, think of one.’ Three times, I tried but I couldn’t. So he said: ‘How about Victor Grossman?’ I didn’t like it one bit, but I was so ashamed I couldn’t think of a name that I went with it. Of course, I didn’t really think then I’d be stuck with it for life.”

Grossman’s flight eastward in 1952 isn’t surprising in some ways. He grew up in a left-leaning family and studied at Harvard University in the 1940s, becoming heavily involved in socialist politics. After graduation, he worked in a factory, trying to organise workers but soon afterwards, was drafted by the US Army when the Korean War began.

With America in the throes of the leftist witch hunt led by Sen. Joseph McCarthy, Grossman was asked to sign a statement saying he had never belonged to any of a long list of left-wing organisations. “I was a member of at least a dozen of them,” Grossman told The Local.

He signed the statement, saying he felt he had no choice as a draftee at the height of the Cold War. “I was frightened; to be known as a ‘Red’ in the army during the Korean War was almost worth your life.”

While stationed near Nuremburg in 1952, Grossman’s secret eventually came out. Though he had just months left before his enlistment ran out, he received a letter summoning him the next week to a judicial proceeding for his communist ties. The penalty for lying on that security form was as much as five years in prison.

Swimming the Danube

Scared, the 24-year-old Grossman slipped away from his base in West Germany and made his way to Austria, which was still under occupation by the four Allied powers. The American zone was separated from the Soviet zone by the Danube River and Grossman simply swam across unnoticed.

“The funny thing is that I didn’t find any Russians around, I thought they’d be waiting there, if not with tanks then with machine guns, but no one was there,” Grossman explains. After several hours wandering, he was picked up by Austrian police who turned him over to Soviet forces.

Grossman spent two weeks in a Soviet jail in Austria while they decided what to do with him. Then, without asking, they took him to Potsdam outside Berlin. There he spent two months being questioned by Soviet interrogators.

A stint in the Saxon town of Bautzen followed, where deserters from other Western armies were also housed. Many were “troublemakers” who had fled east to avoid military justice. While in Bautzen, Grossman met the woman who would become his wife until she died this past August. They moved to Leipzig, where he studied journalism at what was then known as the Karl Marx University.

“I’m probably the only person in the world who received degrees from both Harvard and Karl Marx Universities,” Grossman quips.

After completing his degree, Grossman and his wife Renate moved to Berlin in 1958, where they raised their two sons in a time of relative prosperity.

“Up until the 80s, the standard of living had been rising, not always fast but steadily. But then you could see the economy was getting worse and prices were rising and goods getting scarcer.”

An American jester in communist East Germany

Though Grossman says he was committed to the socialist ideals of the East German state, he never joined the country’s SED communist party and he claims he often made critical remarks in the interest of promoting constructive change.

As an American, “I was a bit like a court jester, able to say the things everyone knew but no one wanted to say themselves,” says Grossman.

Though not blind to the failings of the East German state, Grossman still regards much of the past 20 years as a step backward for those living trapped behind the Berlin Wall. He points to his two sons, both of whom lost their jobs after East Germany collapsed.

“It’s been very rough, as it has for millions of people in the East, millions of people have suffered greatly since the Wall came down, I don’t know if that’s well known in the States,” Grossman says.

But ironically it was the fall of the Wall in 1989 that helped resolve Grossman’s fate. It was only in 1994 that the US Army agreed to drop the charges of desertion against him. He has since reclaimed his US passport and has travelled to America several times, including a visit to a college reunion at Harvard and a book tour to promote a memoir he published in 2003.

“I’ve always thought of myself as American, not German. I thought of myself as a political refugee, not an immigrant,” emphasises Grossman from his easy chair overlooking Karl Marx Allee.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments