Sweden – the most successful society the world has ever seen. That was the startling view of one columnist on British paper the Guardian, impressed by Sweden’s high taxes, wealth redistribution and public services. Indeed, for many social democrats, this corner of Europe is as close to utopia as it is possible to come.

But as with all the other stereotypes – the blondes, the sexual permissiveness, the manic depression, the boozing and the darkness – the idea of Swedish perfection has often been due to people projecting their own agendas onto a country about which they know relatively little.

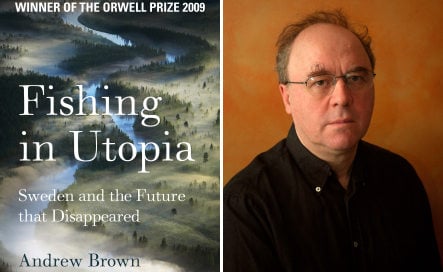

English journalist Andrew Brown is an exception. He lived in western Sweden in the 1970s and 1980s, and makes frequent trips back. His book, Fishing in Utopia, gives a more personal and nuanced account of the Swedish model, and this spring it won him the prestigious Orwell Prize for political writing.

Brown came to Sweden with his girlfriend in the late 1970s at the age of 22 – a love refugee, in the current vernacular. He settled first in Nödinge, a suburb of Gothenburg before moving to the rural town of Lilla Edet. Here he started a lifelong love-hate relationship with Sweden and its unique brand of social democracy.

When Brown moved to Sweden, he found the Swedish model at its zenith. Unions were strong and Olof Palme dominated the political scene. In one wonderful passage, Brown describes how Palme devoted his career in Swedish politics to ensuring that no Swede would ever need to experience the American combination of material poverty and boundless optimism.

“He succeeded so completely that when he died, he left a country where no one was poor and no one had room for optimism.”

Brown elegantly describes the perplexing, frustrating, enchanting and illuminating aspects of moving to Sweden, touching on his work in a timber yard, his marriage, his son and above all his love of fishing.

“I spent years not writing it because I wanted to get away from policy and make it more about people,” he says.

Sweden’s brand of politics and the deep social patterns that underpin it permeate even the most domestic chapters. Brown weaves together his experiences in the seventies and eighties with an account of a trip round modern Sweden. He reflects on how the country has changed due to globalisation, immigration and the slow wearing down of the Swedish model.

Brown’s first few months in Sweden were tough, not least because of his initial difficulties mastering the language.

“I was in hell, apart from Anita [his wife]. I wasn’t among people who spoke English. It drove me mad trying to work out the difference between ‘hans’ and ‘sin’ [Swedish for his and his/its].”

“Lots of my memories are of extreme loneliness. Fishing was a way to deal with that as well as to meet friends later.”

But loneliness, as he points out in the book, is at the heart of the Swedish experience.

“The idea of relating to strangers for pleasure did not figure largely,” he recalls in the book. It was not deliberate unfriendliness, but a society where people just didn’t know how to talk to each other.

Many aspects of the Sweden Brown describes remain recognisable today. Socialism, republicanism and tee-totalism were the foundations of society, and reminders of them were everywhere.

Like many foreigners today he was perplexed by the Systembolaget state alcohol monopoly, which in those days displayed graphic depictions of how alcohol could wreck your body.

The pervasive power of Arbetarrörelsen, the labour movement, was much in evidence in the 1970s. You could run your entire life through the labour movement: in addition to being governed by Social Democrats and being a member of an affiliated union, you could bank at the Coop bank, shop at Konsum and live in a flat owned by the workers’ movement.

While elements of this system remain in place, Brown insists that the Sweden of today is greatly changed:

“You don’t really hear words like nykterhet or solidaritet” today, he says, referring to the Swedish words for temperance and solidarity.

“The Swedish model had right-wing components,” like deference and authoritarianism he argues. This, he thinks, is something that many international fans of the Swedish model fail to recognise.

“You had internally-imposed conformity. It was quite easy for the Social Democrats to tweak the definition of what was acceptable.” There was no real acceptance of pluralism, he says. There was only one socially acceptable view on matters such as women’s rights and immigration.

Brown admits to mixed feelings about Swedish conformity: “When you’re inside it you hate it – it’s oppressive, but when you move away you see the virtues of it. I’ve given up trying to decide whether it’s good.”

Brown’s descriptions show how little – and how much – Sweden has changed in the past few decades.

Returning to Sweden in 2007, Brown found one thing had transformed Sweden more than anything else: immigration. Indeed, the numbers involved are astonishing – Sweden received 96,000 people in 2006 and 99,485 in 2007, the highest numbers since records began in the 19th century.

“I know it’s changed Sweden. In some ways it has made Sweden worse – more dangerous, more criminal. But it has also made it broad-minded and more interesting, and the food’s better.”

“Really, though, I don’t know whether immigration has been good or bad.” What he does find problematic is that mainstream politicians don’t really know how to talk about the issue.

“There’s a significant undertow and I don’t think the political class knows what to do about that. The other thing is that it’s being talked up by the Eurabia crowd.”

Despite his ambivalence towards immigration, he insists Sweden’s a lot less distinctive than it was, due to internationalisation, even to American television.

“There has been a general coarsening of society and a huge growth of inequality.”

But couldn’t the same be said of everywhere?

“I’m talking specifically about Sweden, partly because it used to be so much more deferential.”

But if Sweden has changed, Brown’s beautiful descriptions of Sweden’s wilderness in his passages about fishing give a sense of constancy.

“It was a way of writing about Sweden that has nothing to do with policy. Go in this way and there’s no socialism, no blondes and no ABBA.”

Quite a thought.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments