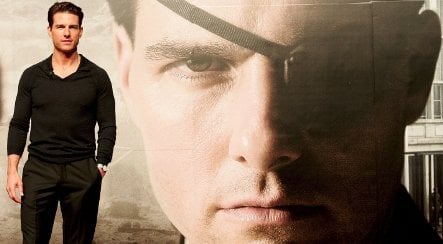

The lights were on late in Berlin’s Otto-Suhr-Allee last week. It is always an exciting moment for Scientologists when Tom Cruise is in town. But the true believers must have been rubbing their hands in glee this time though. The Hollywood heavyweight was in the German capital for the premiere of his film “Valkyrie,” in which he portrays failed Hitler assassin Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg.

A top Scientology fund-raiser starring as a modern German hero! School classes will no doubt file into the cinemas, pre-teenage girls will fall in love with him – a coup for the quietly subversive propaganda machine of this strange sect that feels so persecuted in Germany.

As it happens, I have never had anything against tiny Tom playing Stauffenberg. As far as I’m concerned he could play the Pope – though he would have to improve his German accent. Cruise is an actor and not a bad one, providing he sticks to his strengths: the action hero.

The Scientology thing doesn’t really bother me either. They keep out of my way when I pass them on the Ku’damm, perhaps recognising that my stress-levels are so astronomically high they cannot be cured by their voodoo “Dianetics” therapy. And the film is not bad. The problem is not that Cruise is a brain-washed Martian playing a Swabian aristocrat. The problem isn’t even that we know the ending (note to younger readers: Adolf Hitler lived another nine months after Stauffenberg’s failed attack). No, the problem is that he has made Stauffenberg into an American hero, the kind that keeps cinema audiences gripping the edges of their seats as he tries to save the world.

But Stauffenberg was a German, not Hollywood, hero and his motivation was an old-fashioned one: to save the honour of a military caste which had been discredited by its subservience to Hitler and some of its dubious activities on the Ostfront. The Stauffenberg story is about honour. Little wonder that Cruise doesn’t quite get this right – honour in Hollywood is something that is left to lawyers. But younger German audiences also seem baffled by the concept.

For the same reason, there was general confusion across the country when troubled German billionaire Adolf Merckle recently killed himself. I was stuck in a railway carriage next to a couple in their thirties when they started to discuss the Merckle case.

“He would still have had hundreds of millions, that’s no reason to commit suicide,” said the woman passenger, slapping the cover story of Der Spiegel magazine, which had called the end of the businessman “an archaic death.”

“Yeah,” said her male companion. “He could have enjoyed his life. Bought a yacht.”

I resisted the temptation to slap the man. Plainly, Merckle could not bear the thought that he had let down his grandfather and father who had established a successful pharmaceuticals firm. The breaking point was not the loss of billions of euros, the disappointment of his children or even the loss of his employees’ jobs. It was the forced sale of Ratiopharm which spelled the end of a family tradition. He had wanted to earn the approval of his dead father but had failed himself, through personal weakness and bad decision-making.

So he threw himself in front of a train – as a matter of honour.

Not many of us, I suppose, want to see Germany embracing a Japanese hara-kiri culture. But would a bit of the ol’ seppuku be so bad if we recovered the idea of honour? Not just dying for an ideal, but also sacrificing one’s personal goals? Was there any sense of honour in the way that the Social Democratic Party’s Andrea Ypsilanti behaved in trying to become the premier of Hesse? Many of us felt a chill run down our spines as she delivered her final statement earlier this month essentially shirking blame for a year of political chaos in the state.

Politicians used to bear responsibility not only for their own actions, but also for those in their department. Now we have a financial crisis that has been encouraged by the slipshod control exercised by the political class. The consequence is that millions of people across Germany and Europe will lose their jobs. Yet not a single politician, not a single central banker, not a single member of the financial regulating agencies, has offered his or her resignation. Politicians do step down – but only after the media have made them an embarrassment for their parties. There is no internal code.

Honour is an unspoken contract, a duty conferred on you, usually because you occupy a position of privilege or responsibility. There is a period of political instability approaching. So far protests have touched only Bulgaria, Greece, Latvia, Iceland: societies on the margin of the crisis. But they share an anger about the political class, its failure to anticipate an economic disaster.

Politicians and bankers have to start answering questions and accepting blame otherwise the loss of trust in financiers will become a more general contempt for Europe’s leaders. Before that happens, all politicians have to start doing the honourable thing.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.