Sweden’s bellicose King Karl XII, who ruled this country from 1697 to 1718, was surrounded on Tuesday by thousands of hip-hop kids from the suburbs, who packed the public square dedicated to his memory in the centre of Stockholm.

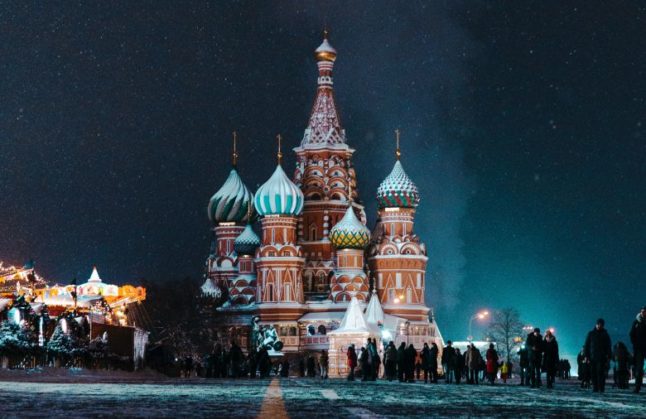

On most days, a bronze statue of this king reigns in lonely majesty in Kungsträdgården, a pigeon on his head. One of his arms points the way towards Russia on the opposite side of the Baltic Sea.

During his tenure on the throne, King Karl XII took up arms against Peter the Great of Russia, leading an assault against Moscow. He is the chap who also defeated Denmark, Norway and Poland. The Swedish Army met its nemesis at the pivotal Battle of Poltava, where Karl was wounded; he eventually fled south to the Ottoman empire.

Karl found refuge in Bender, located in Turkey. It was somehow appropriate therefore to see the bronze statue of this king virtually surrounded earlier this week by throngs of second-generation Swedes taking part in a four-day youth festival, many of whom come from immigrant families with roots in Turkey.

If one lives in a blessed country like Sweden, which has enjoyed continuous peace for over 200 years, it is tempting to imagine we are part of a happy and privileged continent where war is an aberration and an anachronism. Of course, that is just a fantasy with no basis in history or geography.

Earlier this week, as Russians battled Georgians with tanks, fighter jets and field artillery, we were unhappily reminded that this chunk of real estate has deeply ingrained bad habits—bad habits like war, genocide and racism. Europe’s dark history is why all of my four grandparents left Europe in the first place and moved to the United States.

I was reminded of my own clan’s wanderings on the planet as refuges and immigrants when I got a visit this week from my older cousin Richard, who lives in New Haven, Connecticut.

Richard told me cool stories about our grandfather Louis who came from a town near Odessa, located in modern-day Ukraine. Together with eight or nine of his brothers, they emigrated first to a farming community in Argentina, where Louis became something of a cowboy, and earned a nickname, “Long Knife” (Cuchillo Largo).

Perhaps Louis got into trouble or simply didn’t like the South American climate, but he moved to Turkey (following the example of Swedish King Karl XII), where he became a rug merchant.

Granddad next shifted to Canada, travelling the country as an itinerant peddler, finally settling for good across the border in the USA, where he went into the shoe business.

All four of my grandparents learned English as adults, just as I learned Swedish as an adult. Some of my relatives enjoyed far more eventful lives than me, crossing European borders illegally to escape the Gestapo. Like most Yanks, my family’s roots—for better and worse– are on the Eastern side of the Atlantic Ocean.

I bring up my personal trans-Atlantic history not because it is so unusual but because it is so typical. People have always sought to build lives in faraway places because of necessity or choice.

National identity seems to me an artificial construction, a means to unite a tribe or nation to achieve goals we cannot reach individually. Goals like building roads and bridges, running hospitals and slaughtering our neighbours.

This week, when tens of thousands of Europeans fled across yet another border for the umpteenth time in modern history, I briefly felt a silly desire to play that old John Lennon tune “Imagine” about the dream of a more peaceful world. Yes, why don’t we bury all those lovely national flags—even the bright and cheerful Swedish blue and gold banner—and find other ways to amuse ourselves.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.